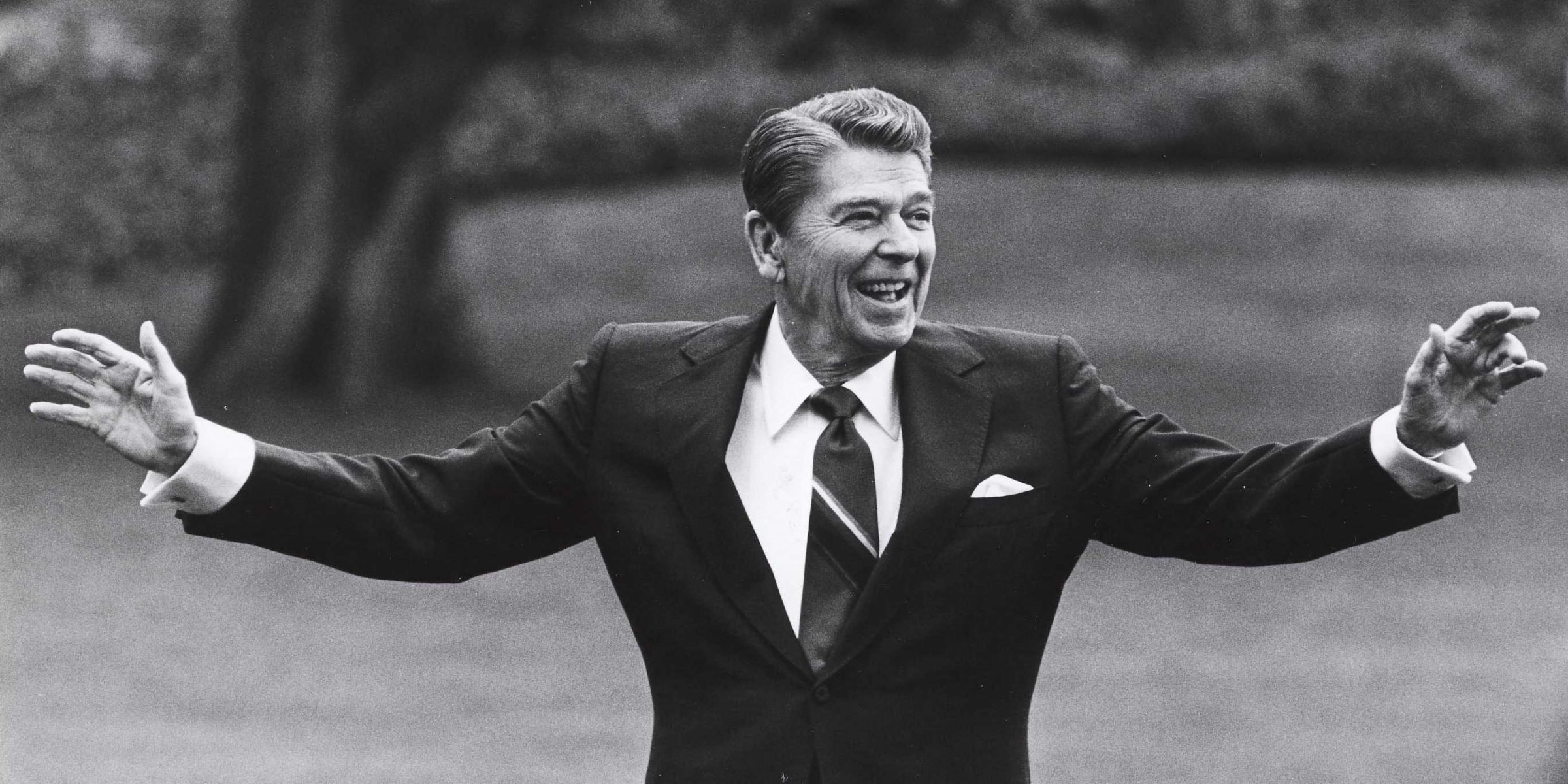

Ronald ReaganREUTERS/Joe Marquette

Ronald ReaganREUTERS/Joe Marquette

A lot of Republicans in Congress cite the Tax Reform Act of 1986 as a model for the tax plan they hope to implement in the next few months. They lament the fact the tax code hasn’t been overhauled in 31 years, and say they want to do it again.

But there are three very large and important differences between the 1986 reforms and the plan Republicans are considering today.

- The 1986 reforms raised taxes on corporations and used the proceeds of that increase to give a net tax cut to individuals. The Republican plan is likely to raise taxes on individuals to give tax cuts to businesses. That is a much uglier sale to make, politically.

- The 1986 reforms were bipartisan — Republican President Ronald Reagan and Democrat Dan Rostenkowski, then the chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, worked together to get them done. There were a lot of industry lobby groups that hated aspects of the reforms and fought to kill them. But the participation of both parties gave each side greater political cover to resist attacks. And the availability of votes from both sides of the aisle meant lots more “gettable” votes could be lost while the reform package still passed.

- The 1986 reforms were approximately revenue neutral and distributionally neutral. They weren’t a windfall for the rich because the large reduction in the top individual income tax rate (from 50% to 28%) was offset by the elimination of tax deductions, higher overall taxes on corporations, and higher taxes on capital gains. We’ll see exactly what’s in the tax legislation to be released on Thursday, but the Tax Policy Center found the most recent version of the Republican plan represents a large tax cut that reserves 80% of its benefits for the top 1% of earners.

I’d note, Republicans and Democrats also spent about two years putting the 1986 tax plan together before they got it enacted. It took a lot of negotiation and planning to build enough support to pass a plan that eliminated lots of deductions and exemptions to pay for lower tax rates.

The more common model for single-party tax policy changes, like Bill Clinton’s tax increase in 1993 and George W. Bush’s tax cuts in 2001, is to make modest changes to tax rates and deduction and credit amounts within the existing tax framework. This approach means you don’t have to fight so many interest groups at the same time you fight the other party.

What Republicans have proposed to do is really hard — much harder than what Reagan, Clinton, or Bush got done on taxes. And Trump does not seem to have the legislative acumen of those prior presidents, either.