When Annie Soisbault imagined herself as a figure in the sporting world, she didn’t see herself as a racing driver—not at first. With seven French junior titles to her name, Soisbault thought she would surely be a tennis champion, competing internationally and taking home coveted wins at Wimbledon.

The problem with tennis was that it wasn’t a very financially lucrative career. She might one day be able to make money in the big leagues, sure, but it was rare for amateur players to make much. Racing, in the late 50s, with its overhanging risk of death and delight at pushing the limits of both technology and the human body to its very edge—well, that was where the money was at.

By the time she was twenty-one, Soisbault had stashed away enough of her tennis prize money to purchase her first two cars: a Delahaye Grand Sport followed soon by the more competitive Triumph TR3.

But she started off small—as small as you can when you’re leaping directly into the 1956 Monte Carlo Rally. She was nothing more than a backup—and therefore backseat—driver to the dynamic duo of Germaine Rouault and Louisette Texier. We don’t quite know how she did it, but when the team hit heavy snowfall in the Ardeche, Soisbault was able to convince her teammates to let her behind the wheel. Whether it was an innate skill at driving in tough conditions or simply that she’d been able to save her energy while the other two competed, Soisbault proceeded to set some damn good times and pass other drivers in the process.

Despite the fact that the trio weren’t classified, Soisbault was so invigorated by her performance that, in ‘57, she started entering races where she was more than just the third wheel. In the Tour de France (no, not the bike race), she and teammate Michèle Cancre finished 21st. In the Coupes de Salon at Montlhéry, Soisbault finished an impressive eighth overall. She even took on the infamous Mille Miglia alongside Monique Bouvier in a Panhard Dyna.

Advertisement

In 1958, Triumph was impressed. Both Soisbault and Pat Moss had been putting in some pretty decent performances behind the wheels of their cars, and they wanted a works driver but couldn’t decide between the two women. There’s a legend that says Soisbault, a master of self-promotion, told them she refused to work with any indecisive team—inspiring them to sign her right away.

It was… not a good year for her. She didn’t place in either the Monte Carlo Rally or the Alpine Rally. It was not a promising start.

So, Triumph shipped her and the TR3 off to the UK for 1959 to try out the RAC Rally. Again—not great. That year’s Alpine Rally? Not great. It was a great relief, then, that she won the Paris-St. Raphaël women’s rally, which contributed toward her European Ladies’ Rally Championship… albeit by exploiting some loopholes in the series rules.

Advertisement

See, there was a clause that stated a certain number of female participants had to start a race in order for points to be awarded toward the Ladies’ Rally Championship. Soisbault, apparently, was notorious for not starting rallies in which she was competing against Pat Moss when she knew her non-start would mean no one got points.

It was not a particularly good look. Annie was, to say the least, not a particularly well-loved woman in the paddock. Especially given the fact that she won the Championship that year, sharing the honor with the only woman to officially drive a Mercedes-Benz, Evy Rosqvist. They’d tied in points.

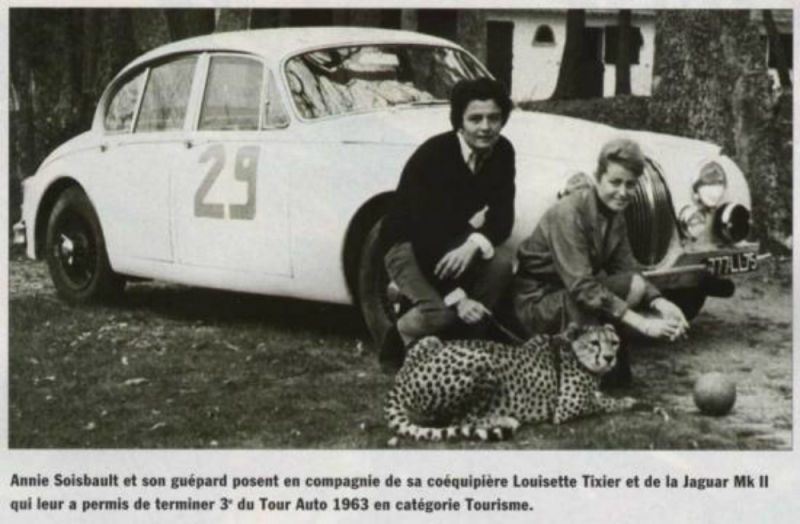

Triumph had had enough of her non-starts in 1960. When she didn’t finish the Alpine Rally yet again, the marque decided to move on to better things. To celebrate, Soisbault teamed up with Texier behind the wheel of an Alfa TI 1300 and proceeded to win the Ladies’ Cup at the Charbonniéres Rally.

Advertisement

Hell, she even hopped behind the wheel of a single-seated, trying her hand at the French Formula Three races behind the wheel of a Lola Formula Junior.

Rallying just didn’t seem to be Soisbault’s thing during the 60s. She turned her focus to sportscar racing and road racing with the occasional foray into rallying—but it wasn’t her main focus.

During that time, she married the Marquis de Montaigu. See, Soisbault was as proficient at the social side of racing as she was at the speed, and that partnership proved to be a damn good career move. The Marquis was, well, rich. If his wonderful wife asked for a Ferrari GTO, then, why, of course he would provide!

Advertisement

It helped that he loved racing, too. In 1965, the duo were teaming up for events across France, everything from rallies to Grands Prix to hillclimbs. And it was at the Mont Ventoux hillclimb that Soisbault became the first woman to ever exceed an average speed of 62 mph on her storm up the cliff.

After that, Soisbault was encouraged to slow down. She was in love, and she’d had a ten-year career behind the wheel. Rather than keep going, she focused on her professional life as the managing director of a Parisian dealership that imported luxury car brands like Aston Martin to France.

Sure, she’d head out to Mont Ventoux once a year to show her mettle, but by 1969, she was done. She hung up her helmet and called it a day.

Advertisement

Soisbault was the kind of female racer that had slowly phased out before her era. She was a fierce competitor, yes, but more than that, she was in it for the adventure. Racing was something she took seriously, but it was also a world that allowed her to have fun, enjoy herself, and taste some of the finer things in life. It was an attitude better fitted to the 1920s and 30s and didn’t always win her favor among her peers—but it did make her a bright figure to watch.

Annie Soisbault died in September 2012 at the age of 78, leaving behind a legacy that speaks to the sheer fun a woman can have behind the wheel.