Buried beneath 4,000 feet of Antarctic ice lies Lake Mercer, a subglacial body of water that formed thousands of years ago and has been long separated from the rest of the world. A project to explore this lake—and its mysterious contents—is finally set to begin later this month.

Called Subglacial Antarctic Lakes Scientific Access, or SALSA for short, the project aims to uncover new knowledge about Antarctica’s subglacial lakes, of which over 400 are known to exist. Over the next two months, SALSA scientists will explore one of the largest subglacial lakes in West Antarctica, a body of water known as Lake Mercer. The team will bore through some 4,000 feet (1,200 meters) of ice using a 60-centimeter-wide drill capped with hot water. In addition to extracting water and mud samples, the researchers will deploy a remotely operated vehicle—a scientific first for a subglacial lake.

Advertisement

The SALSA team is hoping to learn more about these frigid alien environments, such as how water might flow in and out of these ice-covered reservoirs, how life is able to survive under such extreme conditions, the environmental factors under which these lakes formed, and the changing conditions of the Antarctic ice sheet. Importantly, this mission could also serve as a proxy for future expeditions to the ice-covered moons of Jupiter and Saturn—moons that could potentially harbor alien life.

Eleven principle investigators from eight different U.S. institutions are involved in this three-year project, along with a number of international experts. SALSA was founded and funded two years ago by the Antarctic Integrated System Science Program with help from the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Office of Polar Programs.

Advertisement

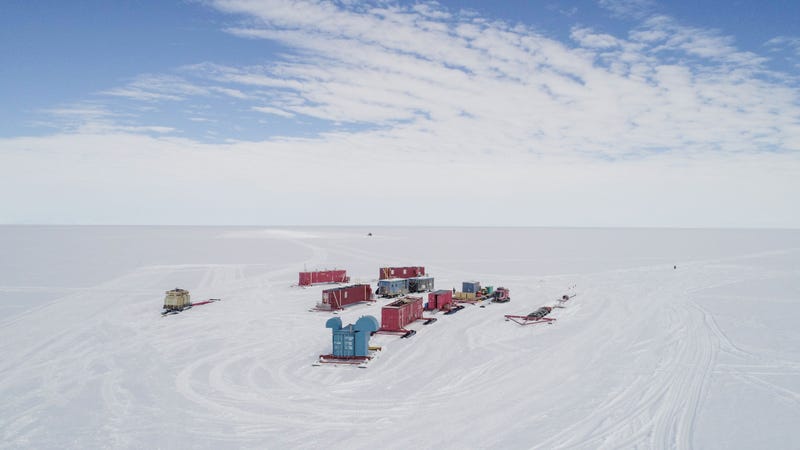

Earlier this week, 21 members of the SALSA science team arrived at Antarctica’s McMurdo Station in preparation for the drilling. From there, personnel and cargo will be flown to the worksite, which is located about 500 miles (800 kilometers) from the South Pole. Should all go according to plan, drilling could start by Christmas. From now until January of next year, around 50 scientists, drillers, and support staff will assist with the project.

Lake Mercer was first detected via satellite more than a decade ago, but it’s never been explored by humans. The subglacial lake measures about 62 square miles (160 square kilometers ) in size, which is over twice the size of Manhattan. But it’s not very deep—just 30 to 50 feet (10 to 15 meters) at its deepest points. The water in the lake hovers around the freezing point, but it never solidifies owing the tremendous pressure exerted onto it from the piles of ice directly above. Lake Mercer likely formed about 10,000 years ago, but it’s a hydraulically active body of water, featuring water replacement times on the order of about a decade (so it’s not completely isolated from the rest of Antarctica). As part of SALSA, scientists will also explore Lake Engelhardt, another large subglacial lake on the Whillans Ice Plain.

Advertisement

SALSA will be the third project to explore an Antarctic subglacial lake; Lake Vostok and Lake Whillans (the latter of which is very close to Lake Mercer and, like Mercer, is also located on the Whillans Ice Plain) were both explored in 2013. Both lakes yielded a surprising number of microbes, and SALSA scientists are anticipating similar findings in Lake Mercer.

Once the drill pierces into the lake, SALSA scientists will extract water samples and mud, as Nature News reports. An ice core sample up to 26 feet (8 meters) in length will help the scientists age the lake and its contents, and show scientists how the lake’s microorganisms are obtaining their nutrients. The remotely operated vehicle will snap photos of the reservoir and use its robotic claw to grasp more sample material.

Advertisement

In terms of the life that could exist in Lake Mercer, the SALSA scientists could definitely be in store for something interesting, as Nature News reports:

Evidence pulled up from the drilling project at Lake Whillans has spawned a series of discoveries that have shaped the current programme at Lake Mercer, 40 kilometres to the southeast. The water from Lake Whillans teemed with 130,000 microbial cells per millilitre — a population 10–100 times bigger than some researchers expected. Many of the microorganisms obtained their energy by oxidizing ammonium or methane, probably from deposits at the bottom of the lake. That was a key insight, because it suggested that this ecosystem—seemingly cut off from the Sun and photosynthesis as an energy source—was still dependent on the outside world in an indirect way.

The researchers who studied Lake Whillans suspect that the ammonium and methane seep up from the lake’s muddy floor from the rotting corpses of marine organisms that accumulated during warm periods, millions of years ago, when this region was covered by ocean rather than ice. Evidence of this food source came from Reed Scherer, a micropalaeontologist at Northern Illinois University in DeKalb, who was part of the Whillans project. He found the shells of diatoms (single-celled algae) and the skeletal fragments of sea sponges littered throughout the lake’s mud. “There is a marine-resource legacy that the microbes are still tapping into,” he says.

Advertisement

In addition, the SALSA researchers will be on the lookout for animal life, which wasn’t detected in either Lake Vostok or Lake Whillans.

Analysis of the microorganisms found within the waters of Lake Mercer could show how life might survive on Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Both moons are covered in ice but feature warm bodies of liquid water beneath. There’s a decent chance that the conditions within Lake Mercer could resemble those found on Enceladus and Europa.

It’s a very exciting project indeed, and we’ll be following the scientists’ progress closely. Stay tuned in the coming weeks and months for updates.

Advertisement