Cruise co-founder and CTO Kyle Vogt said Friday that disengagement reports released annually by California regulators are not a proxy for the commercial readiness or safety of self-driving cars.

Vogt, in a lengthy post on Medium, called for a new metric to determine whether an autonomous vehicle is ready for commercial deployment. The post suggests that the autonomous vehicle company, which had a valuation of $19 billion as of May, is already developing more comprehensive metrics.

The California Department of Motor Vehicles, which regulates the permits for autonomous vehicle testing on public roads in the state, requires companies to submit an annual report detailing “disengagements,” a term that means the number of times drivers have had to take control of a car. The DMV defines a disengagement as any time a test vehicle operating on public roads has switched from autonomous to manual mode for an immediate safety-related reason or due to a failure of the system.

“It’s woefully inadequate for most uses beyond those of the DMV,” Vogt wrote. “The idea that disengagements give a meaningful signal about whether an AV is ready for commercial deployment is a myth.”

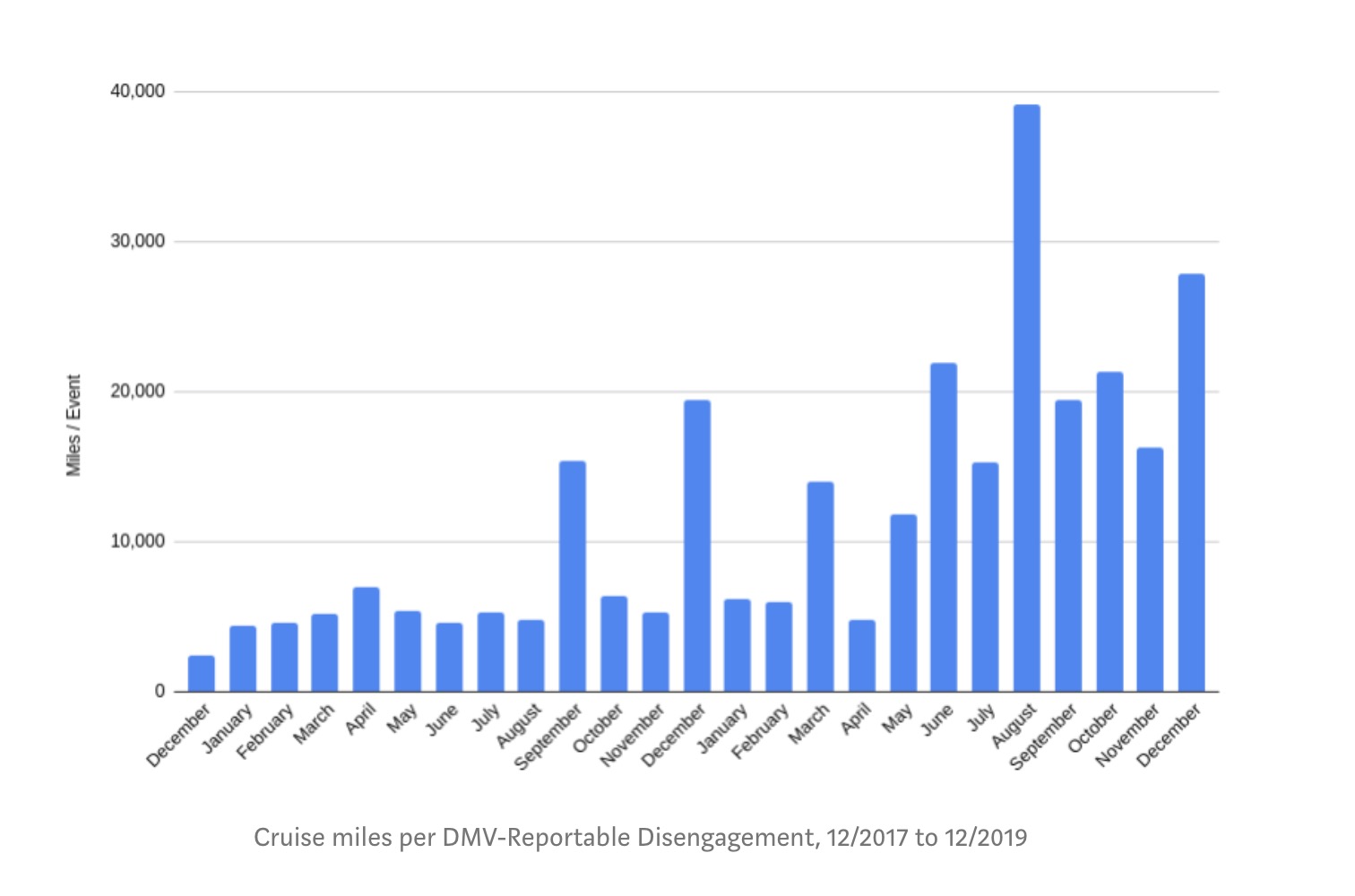

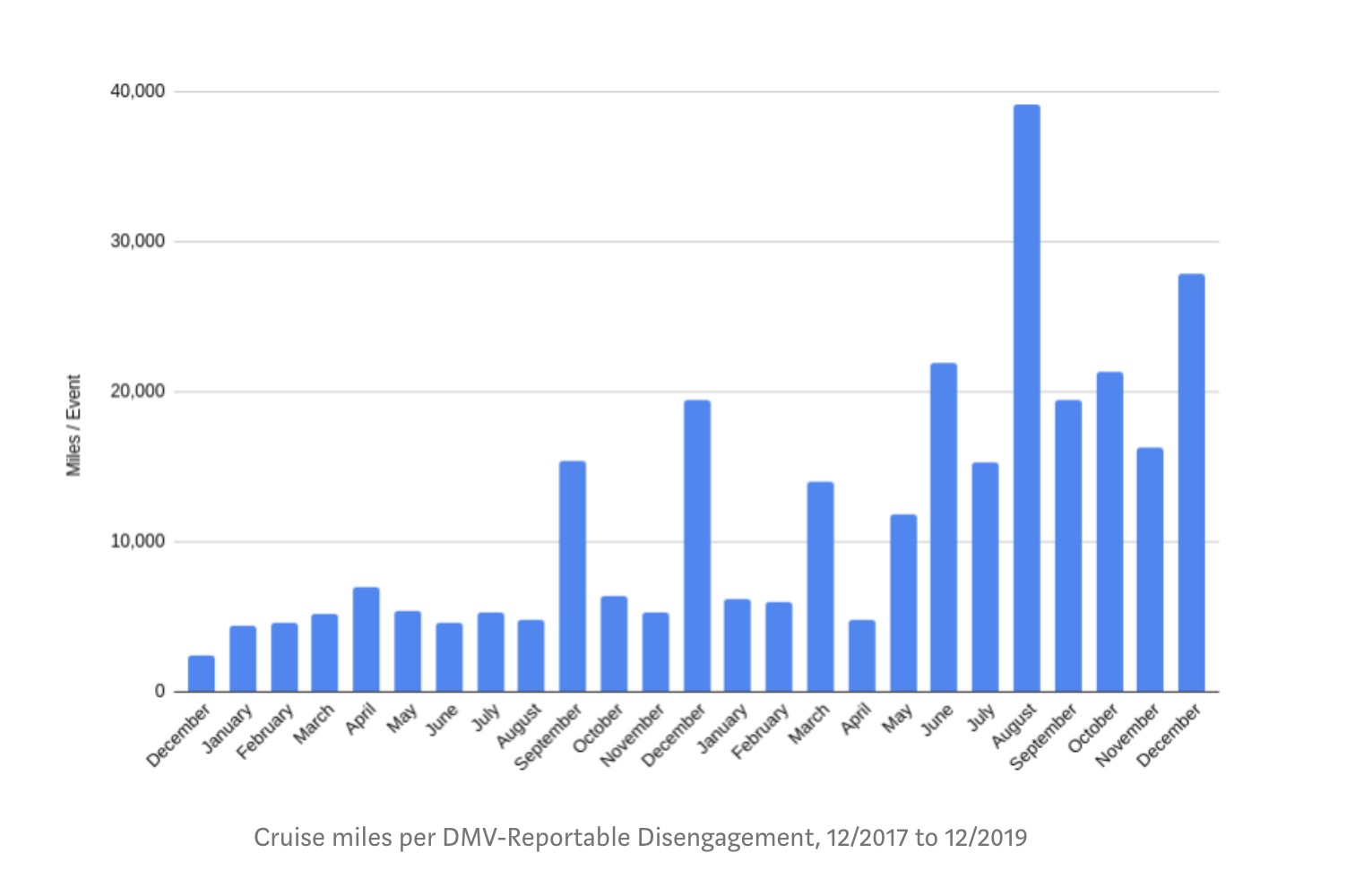

These disengagement reports will be released in a few weeks. Cruise did share some of its disengagement data, specifically the number of miles driven per disengagement event, between 2017 and 2019.

The so-called race to commercialize autonomous vehicles has involved a fair amount of theater, including demos. This lack of data has made it nearly impossible to determine if a company’s self-driving cars are safe enough or ready for the big and very real stage of shuttling people from Point A to Point B on city streets. Disengagement reports as flawed as they might be have been one of the only pieces of data that the public, and the media, have access to.

How safe is safe enough?

While that data might provide some insights, it doesn’t help answer the fundamental question for every AV developer planning to deploy robotaxis for the public: ‘how safe is safe enough?’

Vogt’s comments signal Cruise’s efforts to find a practical means of answering that question.

“But if we can’t use the disengagement rate to gauge commercial readiness, what can we use? Ultimately, I believe that in order for an AV operator to deploy AVs at scale in a ridesharing fleet, the general public and regulators deserve hard, empirical evidence that an AV has performance that is super-human (better than the average human driver) so that the deployment of the AV technology has a positive overall impact on automotive safety and public health.This requires a) data on the true performance of human drivers and AVs in a given environment and b) an objective, apples-to-apples comparison with statistically significant results. We will deliver exactly that once our AVs are validated and ready for deployment. Expect to hear more from us about this very important topic soon.”

Competitors agree

Cruise is hardly the only company to question the disengagement reports, although this might be the most strongly worded and public call to date. Waymo told TechCrunch that it takes a similar view.

The reports have long been a source of angst among AV developers. The reports do provide information that can be useful to the public, such as number of vehicles on testing on public roads. But it’s hardly a complete picture of any company’s technology.

The reports are wildly different; each company provides varying amounts of information, all in different formats. There is also disagreement over what is and what is not a disengagement. For instance, this issue got more attention in 2018 when Jalopnik questioned an incident involving a Cruise vehicle. In that case, a driver took manual control of the wheel as it passed through an intersection, but it wasn’t reported as a disengagement. Cruise told Jalopnik at the time that said it didn’t meet the standard for California regulations.

The other issue is that disengagements don’t provide an “apples to apples” comparison of technology since these test vehicles operate in a variety of environments and conditions.

Disengagements also often rise and fall along with the scale of testing. Waymo, for instance, told TechCrunch that its disengagements will likely increase as it scales up its testing in California.

And finally, more companies are using simulation or virtual testing instead of sending fleets of cars on public roads to test every new software build. The disengagement reports don’t include any of that data.

Vogt’s post also called out the industry for conducting carefully “curated demo routes that avoid urban areas with cyclists and pedestrians, constrain geofences and pickup/dropoff locations, and limit the kinds of maneuvers the AV will attempt during the ride.”

The shot could be interpreted as a shot at Waymo, which has recently conducted driverless demos on public streets in Chandler, Arizona with reporters. TechCrunch was one of the first to have a driverless ride last year. However, demos are common practice among many other self-driving vehicle startups, and are particularly popular around events like CES. Cruise has conducted at least one demo, which was with the press in 2017.

Vogt suggested that raw, unedited drive footage that “covers long stretches of driving in real world situations” is hard to fake and a more qualitative indicator of technology maturity.