Among the revelations in Dark Money, Jane Mayer’s expansive new book on the Koch brothers and the rise of contemporary American conservatism, is that Fred Koch, the billionaire duo’s father, once helped build an oil refinery in Nazi Germany. The New York Times broke that item last week, but left out a key detail from the book: allied forces bombed the refinery during World War II.

According to a formerly classified document obtained by Gawker which corroborates Mayer’s reporting, the U.S. and Royal Air Forces attacked the Hamburg-area facility, known as Europaeische Tanklager und Transport A.G., six times between 1944 and 1945. Koch’s contribution, a so-called “cracking unit” meant for converting crude oil into high-octane fuel, was dismantled after the first round of bombing.

Mayer reveals Fred Koch’s involvement in the refinery inan early section of Dark Money detailing the making of the Koch patriarch’s—and thus the Koch family’s—vast wealth. “Fred Koch’s willingness to work with the Soviets and the Nazis was a major factor in creating the Koch family’s early fortune,” she writes, referencing refineries Fred Koch previously constructed in Joseph Stalin’s U.S.S.R. The implication is clear: the fortune of one of the American right’s most influential families was built in part on work performed under oppressive regimes.

Advertisement

Europaeische Tanklager, or Eurotank, was a converted oil storage facility that sat on the Elbe River, about seven miles northwest of the industrial city of Hamburg. According to Mayer, Eurotank was owned by William Rhodes Davis, an American businessman and Nazi sympathizer, who contracted Koch’s company Koch-Winkler to provide its engineering plans and oversee construction. Construction on the plant began in 1934, about a year after the establishment of the Third Reich, she writes, and its primary client was the German military, to which it sold high-octane gasoline for use in fighter planes and bombers during World War II.

Sponsored

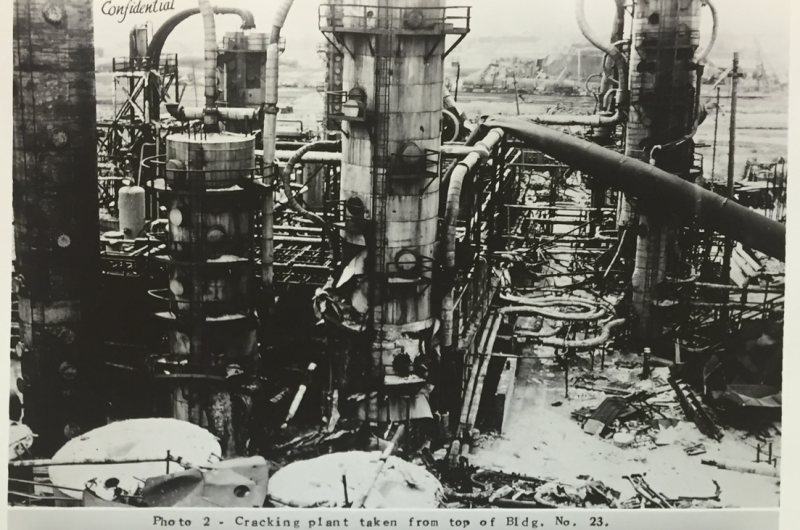

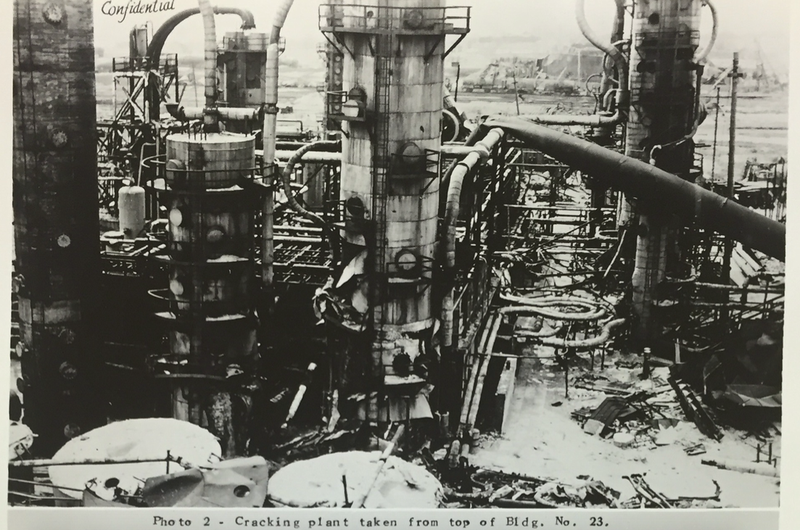

Eurotank was “a key component of the Nazi war machine,” according to Dale Harrington, a Davis biographer whom Mayer quotes in Dark Money. Evidently, the allied forces agreed with that analysis. In September 1945, an expert panel called the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey published a 78-page report on a series of six attacks on Eurotank by the U.S. Air Force and Royal Air Force beginning June 18, 1944, and ending April 10, 1945. The introduction to this formerly confidential document, which was provided to Gawker this week, calls the facility “one of the largest modern oil refineries in Germany,” and estimates that the hundreds of bombs dropped by the allied air forces destroyed 80 percent of Eurotank’s buildings, tankage, and equipment. The attacks also killed one person and injured another, though the casualties “did not affect operations,” the report alleges.

The document also contains about a dozen photos of the damage the refinery sustained during the bombing, which are collected in the gallery above.

After the publication of the Times story about the refinery, Koch Industries CEO David L. Robertson wrote a letter to employees which criticized parts of Mayer’s reporting. Robertson did not attempt to dispute that Winkler-Koch contributed to the building of Eurotank, but alleged that the company was only responsible for the construction of the refinery’s “cracking unit,” not the entire facility. To an extent, the 1945 document seems to prove Robertson right. The Eurotank complex contained two seperate units for processing crude oil into usable fuel: one built by Koch-Winkler and the other by the German company Borsig. (Whether Koch-Winkler was involved in the planning or supervision of construction on the Borsig unit is unclear.)

But the implication that Koch was only responsible for one small cog in a much larger and more complex machine may be misleading. According to the Bombing Survey’s report, the Winkler-Koch unit was rated at a capacity of 360,000 tons of oil per year, while the Borsig unit was rated at just half that amount. Further, Eurotank “contained one of the few thermal cracking units in Germany,” the report reads. It seems likely that this special capability was the work of Fred Koch. In his 2015 book Good Profit, Charles Koch boasts that his father “developed a better thermal cracking process for converting heavy oil to gasoline, one that was less expensive, provided higher yields, and involved less downtime than competitive processes.”

Because Germany did not have enough imported crude oil to make use of all of its refineries, Eurotank did not produce fuel between December 1941 and July 1944. Between that month and bombings in the spring of 1945 that rendered the refinery inoperable, it refined an estimated 114,787 tons of oil.

But the Winkler-Koch unit was taken out before it could be of much use to the war effort. Two bombings in June 1944 damaged the unit, and it was later dismantled for safety reasons. Had Koch’s equipment gone undamaged, it could have more than doubled Eurotank’s production, refining an estimated 250,000 tons of oil between 1944 and 1945. “The capacity of the Winkler-Koch unit can be considered as a potential loss resulting from bombing…When refining capacity became acute and the Winkler-Koch unit was needed, it was not available,” the report reads.

Through its willingness to spend vast amounts of money on extreme libertarian activism, the Koch family has waged a war on the institution of the U.S. government that has lasted decades. Thanks to the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, we now know that way back in 1944, it was the government that fired the first shot.

Images via U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey. Contact the author at andy@gawker.com.