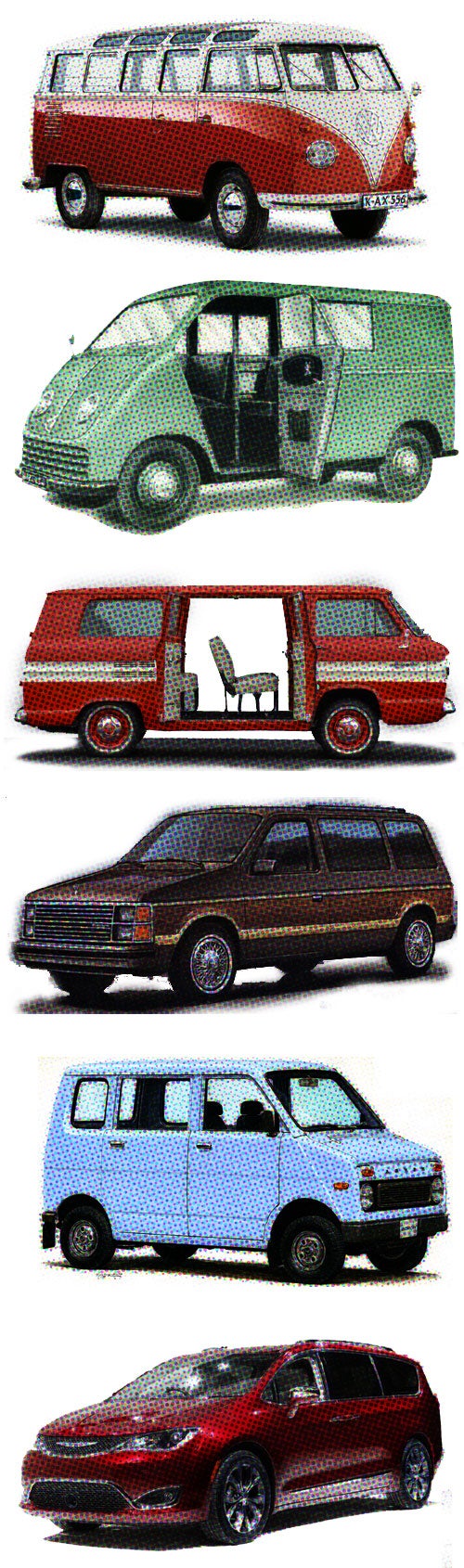

Once people know I’m an auto journalist, usually they ask me two things: First, if my parents were able to get over their disappointment, and second, what they should buy if they need a minivan, other than a minivan. Buying a minivan for their minivan needs is out of the question.

This general concept is sometimes called the Minivan Stigma. At least, that’s what it seemed like the marketing people at Chrysler were calling it when they brought it up over and over again at the Chrysler Pacifica launch event I just returned from.

Chrysler has spent ridiculous amounts of money trying to accommodate this stigma. The main exterior designer explained how every decision—emphasizing horizontal lines to stress width over height, avoiding box-like corners—was focused on the goal of making the Pacifica minivan not look like a minivan. The fact they did this speaks volumes about how fundamentally insecure and self-defeating people can be about their car choices, and I want to end this today. So get ready.

Advertisement

Let me preface everything that follows here with a maxim of mine: Drive what you want.

This is a concept I take very seriously, which is why I happily drive a ridiculously archaic mechanical tortoise with an engine in its ass. I believe everyone should be free to drive a car that doesn’t just get them where they need to be, but makes them feel happy and fulfilled just by existing. I don’t care what you drive, as long as you want to drive it.

Sponsored

Because I take this idea seriously, when I feel like people aren’t really making their own decisions, or are being pressured into a path that either isn’t their own or doesn’t make sense for them, I feel compelled to say something.

And this is what I see happening with the stigma against the minivan and the rise of the crossover: outside forces, ones that play on some of our worse instincts, are driving people to buy cars that make no sense for them, satisfy only desires implanted by dishonest social conditioning, and, in the end, make them less happy.

I was talking to a friend with two children about what cars she wanted, and she freely admitted that when she rented a minivan, her life was measurably easier. Driving the minivan proved to be a fantastic automotive experience. But she personally owns a Toyota RAV4, one of the most popular crossovers sold today.

When I asked her why she deals with a car that, on pretty much every metric that matters, is worse than a minivan, she said something that I’ve heard many times before: She’d never buy a minivan, because that would mean she’s “giving up.”

Advertisement

This is not a person particularly interested in cars. I think she barely thinks about cars at all. But, somehow, she has a strong opinion about never owning a minivan, because she’s been programmed by all sorts of media with the message that minivans aren’t cool, or that owning one somehow means a complete abdication of her individual identity.

This, of course, is horseshit.

What exactly does any think makes the RAV4—or any other indistinguishable SUV or crossover—cooler and more fulfilling than a minivan? The lack of sliding doors? Bigger tires? Higher floor level? A longer hood? These are meaningless. Nobody takes a RAV4 off road. My friend sure as hell never does. The big tires are just more expensive to replace, and the high floor just makes it harder to get your kids, cargo, or whatever in.

SUVs became ubiquitous because a whole generation of people needed minivans but were too insecure to accept that. So they bought huge-tired station wagons on stilts (normal wagons are always great, just FYI) in the hopes that, what, you’d assume they were on their way to fight rhinos in Africa instead of picking their kid up from lacrosse camp?

It didn’t work. It couldn’t have. No matter how much people shudder when they talk about minivans, the truth is that when you see an SUV, you know it’s what people drive to the PTA. So now we have crossovers.

The idea that a crossover is cool is a complete fabrication devised by marketing departments. What, exactly, are people afraid of “giving up” in a minivan that they somehow retain with a crossover? What are they going to do in that crossover that they can’t do in a minivan? Drive more easily over curbs so they can fight crime, or maybe use that slightly longer hood to bone, vigorously and sweatily, in parking lots? No. They’re not going to do a damn thing differently.

The only thing that they realistically can achieve in a crossover is delude themselves into thinking two things: that they can be driving somewhere and look like they don’t have kids, and that anyone even cares whether they have kids or not.

This is a bizarre contemporary obsession, the notion that having kids destroys your chance to be seen as desirable and compelling. Was I even desirable or compelling in the first place? Yet mothers and fathers don’t want to drive minivans because then people would think they were mothers and fathers.

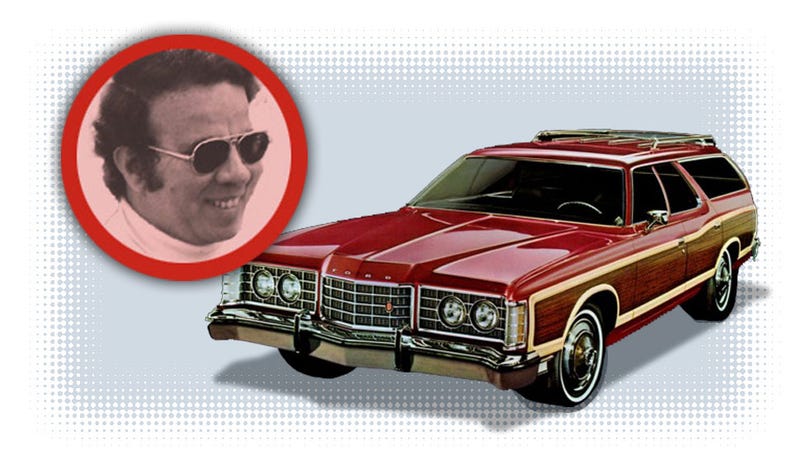

This is a relatively new phenomenon. When I was growing up, my dad had a Ford Country Squire wagon, complete with goddamn wood paneling on the side. My dad was a sort of dapper fellow, and always paid a lot of attention to his clothes and grooming. This was a man quite concerned with his personal appearance.

And yet he never once felt awkward or ashamed to drive what was essentially an eight-cylinder neon sign that read THIS MAN IS SOMEBODY’S FATHER. He was somebody’s father. He was an adult. He never cared whether or not his car was cool, and as a result, he looks like a period-correct badass in every picture I’ve seen of him.

So what happened to us? Why did we decide that a vehicle that makes life with a family better and easier is something shameful? Sure, a minivan is not ideal for autocrossing, but neither is a Tahoe. And, again, if you have a specific personal desire to drive a rally-prepped British Ford Escort Cosworth to the grocery store, I’ll be the first one in line to help you install your baby seat. But if you don’t have strong automotive desires or opinions and you have a family, you’re a tool of the man if you won’t at least consider a minivan.

Hell, without all the baggage and taint of neurotic marketing, you can argue that a minivan is a much cooler vehicle, fundamentally. It’s a mobile room, and as such it’s flexible and ready for anything.

There was a reason there was a huge van craze in the ’70s: Mobile rooms are private spaces where you can do drugs, get laid, play music, whatever. A minivan is something you can drive and park anywhere, but you can also sleep in if you decide to just go explore without a plan and find yourself somewhere unknown.

A minivan is something with enough room and flexibility to carry a whole bunch of your friends, or load your sculpture into, or fill full of tools and wood for a project, or carry your experimental robot or kegs of beer or vats of chili or a pack of dogs or whatever.

Shit gets done in vans. What did the A-Team drive? A RAV4? Fuck no, they drove a van, because a van is a mobile HQ where plans are made, and hands are piled atop one another before everyone screams BREAK! and bolts off to go take care of business.

A minivan is a blank slate. It’s flexibility, it’s possibility, it’s shelter, it can be a party inside or a serious workspace. It’s simultaneously a location and a means to find new locations. A crossover is a perfunctory try at doing these things, always a little too cramped or too restricted to really get it happening.

A minivan isn’t trying to impress you from the outside; it’s a flexible tool to get things done, and those things can become grand, interesting things if you want.

A crossover, on the other hand, is a vehicle born out of insecurity. A crossover is for people who fear that their identity—as a man, as an individual, as someone with sex appeal or edginess or surprise or whatever—is in danger. The truth is, it’s not in danger. Not if it was worth a damn to begin with.

If you know a minivan could make your life easier or better, then don’t be seduced by the manufactured appeal of a crossover. If you’re a mom or dad, own it. You’re a parent. You’re not totally unencumbered anymore, but you’re still you, only now you’ve made a whole new person. Your life isn’t over at all.

I know so many parents who do amazing things. Mark Frauenfelder is an inspiration, for example. He has kids and runs websites and magazines and makes things by hand and keeps his kids involved. Artists like Garnet Hertz, Eddo Stern, Kerry Tribe and, if you’ll let me, even my wife and myself. I still find time to do art installations and have a job I adore and a life, and, sure, it’s busy and occasionally tricky with a kid, but I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Paint your minivan British Racing Green with a stripe and autocross it. Buy one as a single person and find that it’s in that van that you and your friends have the most fun. For the next major minivan launch, I don’t want to hear a presentation from a designer about all the ways they made their minivan not look or feel like a minivan.

It’s time to do away with the minivan stigma. It’s insipid youth-worship that somehow manages to disparage youth, parents, worship, cars, everything. Drive what you want, and drive with pride. Especially if you’re driving a minivan.

Contact the author at jason@jalopnik.com.