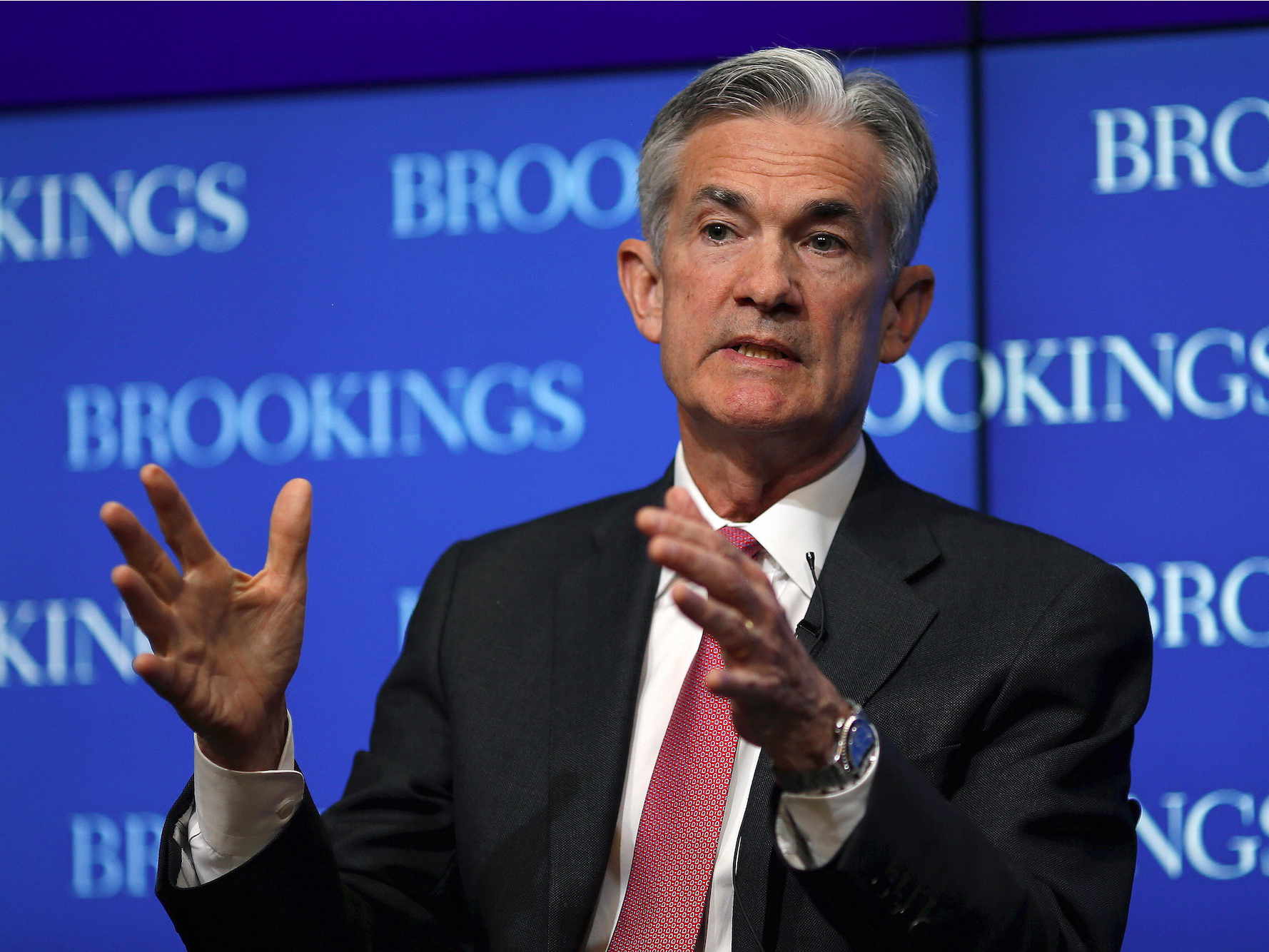

Federal Reserve Governor Jerome Powell delivers remarks during a conference at the Brookings Institution in Washington.Reuters/Carlos Barria

Federal Reserve Governor Jerome Powell delivers remarks during a conference at the Brookings Institution in Washington.Reuters/Carlos Barria

- President Donald Trump has named Jerome Powell to replace Janet Yellen as Federal Reserve Chair

- Powell is likely to face more market turbulence and economic uncertainty than Yellen did during the last four years.

- Yellen’s predecessor Ben Bernanke has warned that ‘the current monetary toolbox’ might not be sufficient to navigate what’s ahead.

Maybe not being reappointed Federal Reserve Chair will prove a blessing for Janet Yellen.

President Donald Trump has named Jerome Powell, a current Fed governor and former private equity executive, to lead the central bank for at least the next for years.

Wall Street welcomed the pick as signaling continuity with the current low-interest rate environment and take it slow approach that Yellen has overseen.

Still, the next four years could be a lot tougher for the central bank than the last four.

Over the past few years, the economy and stock market have been marked by stable growth and a distinct absence of financial distress. But stocks won’t carry on like this for long and there are already signs of financial instability in corners of credit markets. Moreover, the central bank is only just starting its process of unwinding its massive quantitative easing plan, an uncertain proces that could increase volatility.

“The markets have been remarkably ebullient for the past year,” Benn Steil, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, told Business Insider. “Not just stocks. Everything that’s liquid is hot. Meanwhile, corporate long-term fixed asset investment is still subdued. This suggests that there’s a lot of cash out there searching desperately for yield without commitment.”

That’s great for markets in the short run but will eventually become a problem.

“Whenever everyone thinks ‘well, it’s liquid – I’ll get out before the trouble hits,’ problems occur,” said Steil. “So there is, to my mind, a good chance Powell will have to deal with far more turbulence than Yellen has.”

One of the biggest concerns for Fed officials about fighting the next recession is a potential lack of tools to combat an economic downturn following a deep recession that forces the central bank to not only slash official interest rates to zero for several years but also to sharply expand its balance sheet to $4.5 trillion.

On Wednesday, the Fed kept interest rates on hold in a 1% to 1.25% range, having raised official borrowing costs four times starting in December 2015. The central bank is also gradually winding down its balance sheet starting this month.

“Powell may at some point need to take balance-sheet reduction off auto-pilot. I don’t expect him to initiate actual selling, but I can imagine him pausing roll-off and resuming reinvestment if the economy turns sour,” Steil said. “That will present a communications challenge.”

Speaking after Trump announceed his nomination at the White House Rose Garden, Powell pledged to “continue to work with my colleagues to ensure that the Federal Reserve remains vigilant and prepared to respond to changes in markets and evolving risks.”

Bernanke weighs in

Ex-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, Yellen’s predecessor, who now works in the finance industry, doesn’t think the Fed is sufficiently well equipped to handle the next recession.

In a Brookings Institution blog on Oct. 12, Bernanke proposed what he calls “an alternative framework for monetary policy.” He calls it “temporary price-level targeting” which is effectively an effort to temporarily overshoot the Fed’s inflation target following a chronic period of missing it to the downside, such as has been experienced recently.

The Fed has fallen short of its 2% inflation target for five years, and the central bank admitted in its policy statement Wednesday that “inflation for items other than food and energy remained soft. On a 12-month basis, both inflation measures have declined this year and are running below 2%.”

The chart below illustrates this — with the light blue line being actual inflation, and the dark blue being the target.

Brookings Institution/Ben Bernanke

Brookings Institution/Ben Bernanke

The solution, to Bernanke, while somewhat technical, involves essentially a stronger commitment to meeting that target on asymmetric basis — that is, to tolerate too-low inflation just as little as too-high inflation.

“Low nominal interest rates, low inflation, and slow economic growth pose challenges to central bankers,” Bernanke wrote.“In particular, with estimatesof the long-run equilibrium level of the real interest rate quite low, the next recession may occur at a time when the Fed has little room to cut short-term rates. Problems associated with the zero-lower bound on interest rates could be severe and enduring.”

Low inflation sounds great but chronically low price rises often reflect a weak economic and stagnant wages.

Bernanke adds, rather ominously: “I am not confident that the current monetary toolbox would prove sufficient to address a sharp downturn. We should be thinking now about adjusting the framework in which monetary policy is conducted, to provide more policy ‘space’ in the future.”

That thinking is going to be the job of whomever gets handed the reins of the world’s most powerful central bank.