Rumors that elite professional cyclists have been riding with small, illegal motors tucked away in their bikes have swirled around the pro peloton ever since this infamous truther’s video presented evidence against Fabian Cancellara in 2010. Despite more suspicious evidence occasionally floating to the surface, moto-doping seemed like a fairly improbable boogeyman, something that was too outrageous and silly for anyone to actually try. That is, until Femke Van den Driessche got caught with a seatpost motor at the U-23 cyclocross world championships in January.

http://fittish.deadspin.com/motorized-dopi…

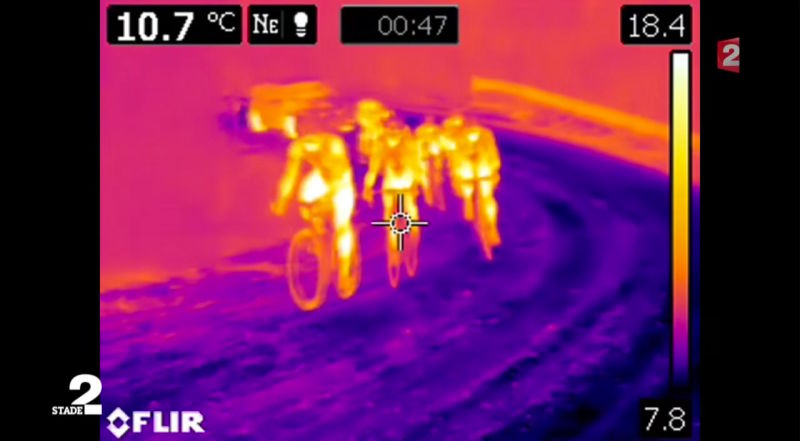

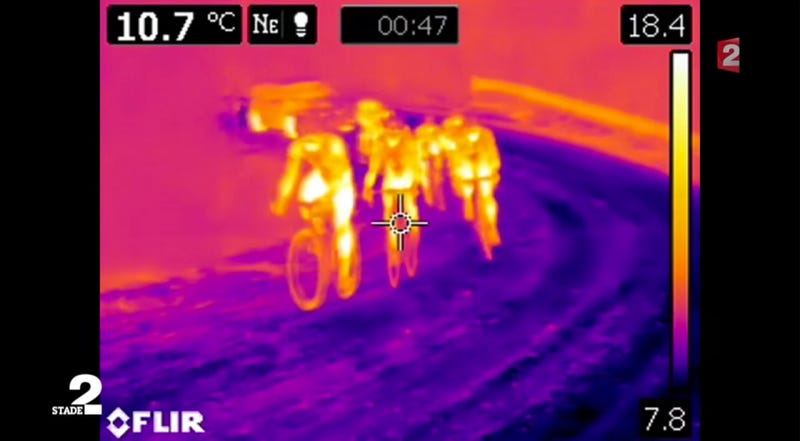

Since then, the UCI has ramped up its testing efforts and they now regularly scan bikes for motors before big races. They haven’t found any, but Italy’s Corriere della Sera and France’s Télévisions Stade 2 carried out a collaborative, rather insane joint investigation, and they claim to have uncovered proof of seven cyclists moto-doping at two races in Italy last month using thermal cameras disguised as television cameras.

Advertisement

Here’s the full 20-minute TV report.

Sponsored

They say that their covert thermal imaging showed five riders using bottom bracket motors (which is what Van den Driessche used) and two other riders using rear-wheel magnet systems. Investigators went to Italy to visit Alessandro Bartoli, who makes €10,000 motors that fit in a bike’s downtube and generate 25o watts. The types of motors that Bartoli makes are cheap and powerful, but they’re relatively easy to detect. The report claims that those who are using that style of motor have found a better, smaller iteration of the Bartoli motor (translated from Italian):

The Austrian engine now has limits: the power is too much and not adjustable. Thermal cameras at Strade Bianche show something different: orange spots in the bottom bracket, less intense and more focused than those produced by Bartoli bike. Spots that turn on and off uphill downhill.

The French TV station also sent a reporter to Budapest to meet with Istvan Varjas, a Hungarian engineer who allegedly supplies top professionals with electromagnetic wheels. Unlike cheating with heavy tube motors, moto-doping via electromagnetic wheels is much more subtle. A series of neodymium batteries are hidden inside the rear wheel, and a coil tucked away below the seat generates an induction force, which gets you 60 extra watts of power. The field is controlled via a bluetooth activator.

Varjas claims that the UCI’s current detection methods won’t pick up on in-wheel moto-doping, but eluding electromagnetic detectors comes at a price. A wheelset from Varjas costs north of €50,000, which is why elite riders are the only market.

In a overly-dramatic segment, the journalists visit UCI president Brian Cookson and show him their findings. He appears concerned, but says that they don’t have conclusive proof. Neither the newspaper report from Corriere della Sera nor the French TV report name names of the seven riders they allegedly caught at Strade Bianche and Coppi e Bartali, but they do swing back to the 2015 Giro d’Italia, which they allege Alberto Contador won with the aid of electromagnetic wheels.

Advertisement

Francetv Sport hoisted a camera into the UCI bike inspection area after Stage 18 of the Giro, where they captured footage of Contador’s lead mechanic slowly inspecting his back wheel then tinkering with his watch (where the bluetooth activator was presumably housed) before the bike was tested by officials. Then, they snuck a hidden camera into an official UCI testing tent, where they filmed what they say is the same mechanic doctoring Contador’s bottom bracket before the official inspection.

This is circumstantial evidence at best, but Contador did lose chunks of time to his rivals in each of the next two stages.

The France Télé-visions reportage closes with new images. They were filmed in Verbania, at the finish of the 18th stage of the Tour of Italy in 2015 when Alberto Contador won the Giro gaining ground on Fabio Aru. A few minutes after the UCI launched a surprise inspection on the bike of the Spanish, under fire for a mysterious change of the previous day’s wheel. The bike was sealed with a clamp and taken behind the stage of the awards, where the UCI had set up a tent accessible only to inspectors. The images show the strangest tinkering Faustino Muñoz, mechanical Pistolero old, around the wheel of the Spanish champions and the clock on his wrist. And then, with a second hidden camera, the “sophisticated” instruments of control in the tent: a hammer with which the same Munoz dismounted the bottom bracket before a distracted inspector.

It’s worth noting that nothing the two news agencies present as proof is 100 percent definitive. They called in a thermal imaging expert to inspect their findings, and he confirmed that they were indeed suspicious. Between the thermal camera footage, the interviews with the engineers who say they’ve sold to professionals, and the suspicious meddling of Contador’s mechanic, it seems like that some degree of undetected mechanical doping is taking place within the peloton.

But for all the indirect evidence that Corriere della Sera and Télévisions Stade 2 present, there’s no smoking gun. They don’t name any of the cyclists that the thermal camera implicates, so there’s no way to verify that the anomalous heat patches were because of motors, even if that’s the simplest explanation. Perhaps this investigation will prompt the UCI to make more careful inspections and actually find the first motor in the professional peloton. So even if we don’t have any confirmation of moto-doping, this hidden-camera investigation raises a lot of very serious questions, and it doesn’t look like this scandal is going to disappear any time soon.