The 1973 Philadelphia Sports Writers Association Awards banquet wasn’t lacking for starpower. Flyers legend Bobby Clarke, who became only the ninth player in NHL history to score 100 points with his 104-point 1972-73 campaign, was one of the honorees. So too was Penn State running back and newly-minted Heisman Trophy winner John Cappelletti. The featured speaker that evening was Joe Paterno, who at the time was the biggest name there was in Pennsylvania sports. One of the award recipients was a jockey named Mary Bacon, who was named the most courageous athlete of the year for repeatedly overcoming brutal injuries suffered on the track. At the podium, Bacon accepted the award, shrugged, and said she wasn’t that courageous. She was just doing what she loved.

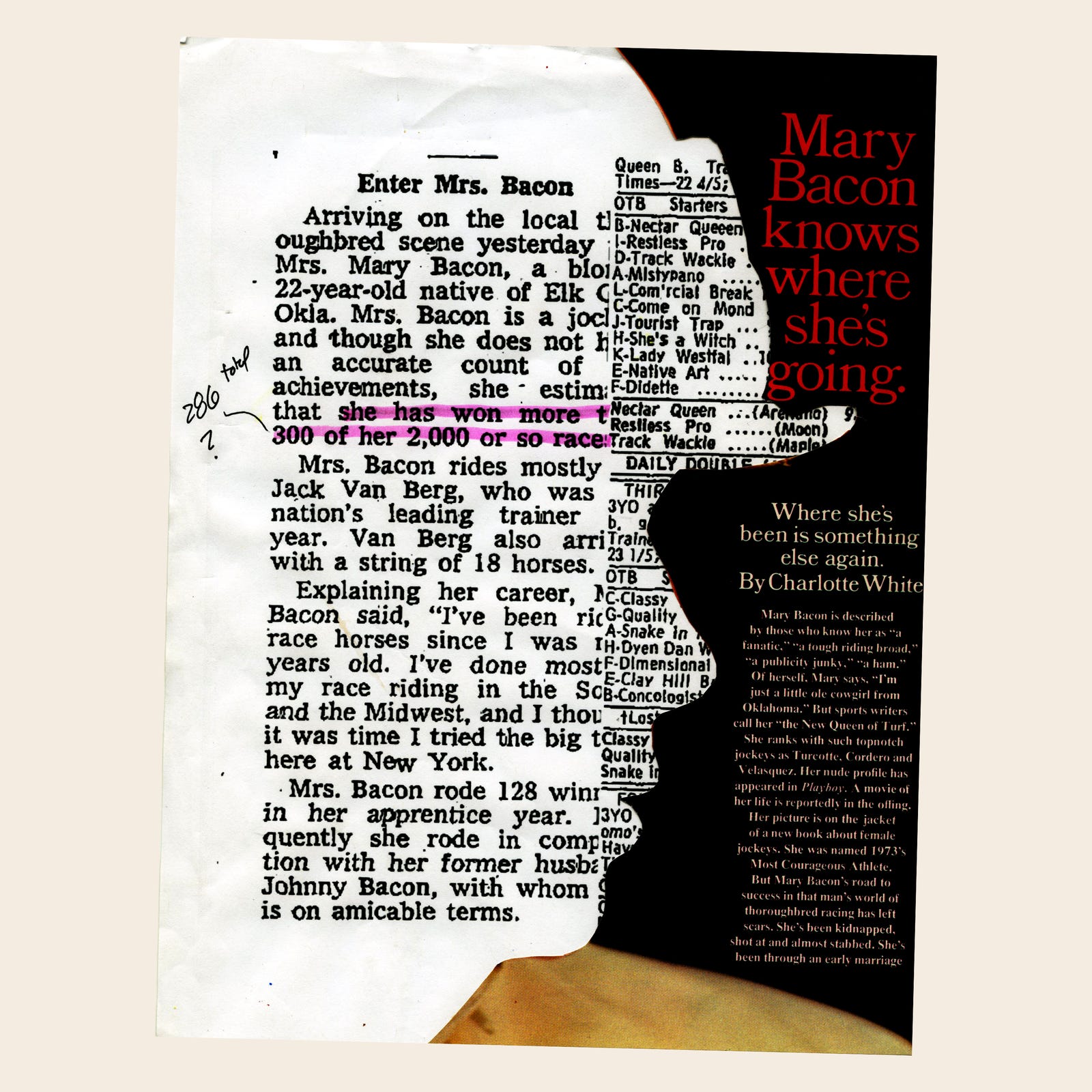

Bacon received the award at the height of her fame. She had been granted her jockey’s license just four years earlier, and in the years since had not only become a highly successful and pioneering rider, but a true American celebrity. She appeared in the pages of Vogue, made it on the cover of Newsweek, captured the attention of sportswriting heavyweights and Hollywood screenwriters alike, posed for Playboy, and scored a sponsorship from Revlon.

Her sudden rise to fame was the result of much more than just her success as a jockey. If there’s one thing Mary Bacon was better at than riding horses, it was crafting her own legend. She was a great interview and a reliable producer of fantastic quotes—two years after divorcing her first husband, she told People magazine, “If they ever legalize marriage between horses and human beings, then I’ll get married again.” She also boasted a backstory bursting with anecdotes of mythic quality.

Take, for example, the incidents that led to her winning that 1973 award. Bacon had been in the tackroom at the Aqueduct Racetrack in New York when someone screamed out that Aegean Queen, a 2-year-old Bacon had ridden before, was choking. Somehow, the horse had the stirrup iron wrapped around her jaw, so Bacon rushed in and pulled it off. Aegean Queen was facing the rear wall when a hotwalker slapped the horse on the ass, and in the chaos, the 1,200-pound animal fell on the diminutive jockey, breaking her pelvis, upper and lower back, and leaving no feelings in her legs.

For nearly two months, Bacon was laid up in a nearby hospital, cocooned in a cast from under arms to ankles. During her recovery, she ditched the institutional clothes and wore racing silks as pajamas. Not even four years into a career that would run its course by the time Jimmy Carter moved into the White House, hospital stays had become commonplace for Mary Bacon.

Nine months before the freak Aegean Queen incident, she was riding Tiger’s Tune at The Meadows outside Pittsburgh in the third, and clipped another horse into the turn. Bacon’s head hit the dirt and she spent the next week unconscious in the ICU with three blood clots on the brain. A few days later, Bacon checked herself out, signed some “official” paper saying it was fine for her to ride, and brought Crafty Cream home to victory on her first mount that night. Someone from the hospital saw her name in the paper and called the track saying she shouldn’t be out there. Bacon packed up her tack and headed to Kentucky. She won three more races that week.

Advertisement

If these sound like calamities befitting a character in a tall tale, it’s because that’s often what Bacon was. Her life was irresistibly fascinating, but the way she recounted it was also riddled with exaggerations and outright falsehoods. To make matters more complicated, the true stories about Bacon are, in many ways, more fantastical than the ones she invented

Mary Bacon took a bullet while pilfering fruit as a child. Mary Bacon dropped out of school in the sixth grade and was pregnant by age 16. Mary Bacon had a romantic relationship with Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard David Duke. Mary Bacon was kidnapped by a stalker. That same stalker later tried to shoot her with a gun. Not all of those sentences are complete horseshit.

The legend of Mary Bacon didn’t persist for very long, though. Her fame dwindled almost as quickly as it arrived, and she eventually became something of an outcast, left alone to manage the consequences of her own actions and the pain inflicted on her by the sport she loved. At the age of 43, Bacon died by suicide in a motel room.

What Bacon left behind is one of the most complicated and confounding legacies in the history of American sports, and any attempt to try and find out who she really was requires digging through the layers of myth, bravado, and sordid decisions that defined her life.My attempt to nail down an accurate portrayal of Bacon’s life began with cross-checking numerous features and news articles against one another, and eventually led me to speaking with a number of people who crossed paths with her during her peak horse racing years, including a fellow jockey, a longtime paramour, a couple of white supremacists, a source close to her family, and her ex-husband’s third wife. It’s unlikely we’ll ever know the true story of Bacon’s life, though, because it’s unlikely that anyone ever got to meet the true Mary Bacon.

“I don’t know if anyone really knew Mary Bacon,” says Jason Neff, a filmmaker working on JOCK, a documentary about pioneering female riders. “I think the race track was so transient at the time that she was probably a little different with whomever she was with. By the time someone got to know her, she was gone to another track. And different places and times probably brought different Marys. I’ve heard so many varying stories, I too wonder who Mary was.”

Advertisement

In May 1969, 21-year-old Mary Bacon received her jockey’s license at Fingers Lakes Racetrack in Farmington, New York. On June 5, she won her first race, although as it turns out, she might have only been 20. Or was it 23? 24? Maybe 25.

Such details were difficult to pin down, because as Bacon’s fame grew so too did the lies and half-truths she told about herself. In Lynn Haney’s 1973 book, The Lady is a Jock, Bacon (both the 10,000-watt smiley cover girl and the subject of its 57-page first chapter) vividly described what her childhood races were like. She elaborated on how jockeys would bring illegal chains and electric shocks to get their horses moving faster, and told the story of a race in which a horse on one side of her had a chicken tied to the saddle, and on the other side tin cans were attached. Bacon explained: “I guess the guy who put me on his horse figured I was as good as a chicken.” She also claimed to have done time on the rodeo circuit, once successfully sustaining her slight frame atop a Brahman bull.

In interviews and profiles, Bacon enumerated the nitty-gritty details of her childhood. In short order: Oft-unemployed father who died in an alcoholic’s ward, an illiterate mother, time in multiple reform schools, foster care, getting shot in the leg for stealing a watermelon, dropping out of the sixth grade (or possibly cheating her way through high school), living in numerous states, and ending up pregnant and married at the ripe old age of 15. Or maybe 16.

Bacon succinctly laid out her background to venerable New York Times sportswriter Red Smith, saying she had, “No money, no education. If I can fight, it’s from getting to the dinner table.”

The great Pete Axthelm ate up similar details and regurgitated them in the pages of Newsweek. The fetching Mary Bacon talked, writers wrote, and even her contradictions left the door open for the nuttiest version of her life to be the one that made it to print.

Here’s a whopper from Haney’s book: Bacon loved The Horsemasters, a 1961 Disney TV movie in which eight teens attend a prestigious English riding school. She became obsessed with steeplechase, applied to the school, and got in. The term started in January, so Bacon needed to make money to cover tuition. She spent the fall working at Detroit’s Grosse Point Hunt Club, galloping horses in the morning, teaching equestrian classes during the day, and working as a go-go dancer at night. Needing more bread, she started hiring herself out for private parties, where for $25-$75, she would jump out of cakes topless. A few years later, Bacon was sitting in the Detroit Racecourse Club when a well-heeled businessman recognized her and enthusiastically reminisced about seeing her shake her moneymaker.

Advertisement

Yet after the book was published, Bacon told the Louisville Courier-Journal, “That stuff was a bunch of horse manure. Can you tell me why someone would want a flat-chested little girl like me to jump out of a cake?”

“Yeah, she made that up, but that was Mary. She was a very funny person and a really great storyteller,” says Steve Rowan, a jockey and trainer who says hehad long-running affair with Bacon.

“I was in the first race she ever rode. We didn’t know one another, but in the gate she looked at me and said, ‘Rowan, I’m going to beat your ass!’ She didn’t, I won. But you just never knew what was going to come out of her mouth.”

As for that hardscrabble upbringing, it was lifted straight from the biography of Mary’s first husband, Johnie Bacon. At least that’s what Johnie’s third (and last) wife, Susan Bacon, says. “The poor Okie family is Johnie Bacon’s story. He was the top bug boy, apprentice jockey, in the country at the time, and Mary wanted to use his status, so she seduced him when he was still a teenager,” claims Susan. “I ran in the same circles as Mary and it was known she lied all the time.”

It was Charlotte White, a writer for womenSports, who eventually nailed down most of the facts of Bacon’s biography in her 1974profile of the jockey. White spoke to members of Bacon’s family while reporting her story, and quoted Bacon’s own mother saying that her daughter took liberties with the truth after getting “caught up in that whole New York scene.” As the mother put it: “You know—bad girl makes good. She’s a real ham.”

Advertisement

In response, Bacon told White the woman she spoke to wasn’t her mother, who died in childbirth, but rather just a “nice lady” she had befriended.

Here’s what White was able to nail down: Mary Bacon was born Mary Steedman, in the affluent Chicago suburb of Evanston, on February 9, 1948 (making her 26 when she was on the July 1974 womenSports cover.) She was raised in Toledo, Ohio in a close-knit prominent family whose lineage includes General James Steedman, a heralded Union Army Civil War General whose statue watches over Jamie Farr (aka Corporal Maxwell Q. Klinger) Park. Her father was a pianist with a 15-piece band who later went into construction, and was active in local youth sports, including organizing swimming meets where Mary set records. She also took ballet and acrobatics. It was an athletic family all around—her mom was a former dancer who founded the local arthritis foundation with her sister. Mary had two siblings, a sister, Suzix, who went on to become an equestrian trainer in California, and a brother, Jim, who would wrestle for the University of Cincinnati.

In White’s article, the elder Mrs. Steedman said the family owned horses, belonged to an elite riding club, and had Mary on quarter horses by age five.

In high school, Mary got a job as an outrider at Toledo’s Raceway Park, helping with the morning workouts and leading the animals to the starting gate. After graduation from DeVilbiss High School in 1966, she worked at Grosse Pointe, saving money for her season abroad. At Porelock Vale in Somerset, England, she studied steeplechase, stable management and veterinary medicine, passed the government’s exam, and returned to Michigan a certified British Horse Society Assistant. In addition to teaching fence-jumping to Detroit’s upper crust, she galloped ponies for Pete Maxwell, a renowned trainer who also employed a bug boy named Johnie Bacon.

Mary liked to claim that she and Johnie got together a few years after working together, when they reconnected while galloping against one another in the Okie bush races. In reality, they only knew each other for a few months before they were married. According to the (non-conflicting) accounts from Haney and White, Mary and Johnie were hitched on the day after Christmas, 1967. To avoid parental detection, the couple eloped to Canadian, Texas. At 17, Johnie was underage, so they had a stable groom act as his father. He was so drunk he misspelled Johnie’s name (or Johnie’s father’s name, that detail shifted), and she signed the marriage license “Mare.”

Advertisement

The newlyweds settled into in the equine world. Mary went back to working for Maxwell, and Johnie kept plugging away at various tracks, his wife at his side. Everything changed in January 1969, though, when a landmark court case opened up the world of jockeying to Mary.

After suing the Maryland Racing Commission in 1968, Kathy Kusner, a member of the U.S. Olympic equestrian team, won the legal right for women to ride in parimutuel races. She was the first licensed female jockey, but a broken leg sustained in a jumping competition at Madison Square Garden kept her from being first on the turf. On February 7, 1969, Diane Crump became the first female jockey to compete in a professional thoroughbred race, riding 48-1 longshot Bridle ‘n Bit at Miami’s Hialeah Park, finishing ninth out 12. She needed a police escort to get through the crowds. The amazing lede in the United Press International story read:

The track bugler raised his horn to his lips, but didn’t blow the traditional call to post. Instead, he blared out “My Diane,” and the walls of male invincibility on American Thoroughbred tracks came tumbling down.

The following year, Crump would become the first female rider in the Kentucky Derby. She was one of a handful of pioneering women, like Barbara Jo Rubin, who, on February 22, 1969, became the first female jockey to win a race, atop Cohesion at West Virginia’s Charles Town Race Track. According to Haney, the track owners gave Rubin a Camaro as a thank-you gift for all the publicity she brought them.

Although she certainly would’ve wanted to be, Mary Bacon wasn’t there from the bell because she was pregnant. She still galloped horses, but couldn’t bring herself to waddle into her local steward’s office. Bacon was riding on the morning of March 4, 1969, the same day her daughter was born. (Given the itinerant jockey lifestyle, Mary’s severely autistic daughter would later be raised by Mary’s mother and sister.) Within a couple of weeks, she was at it again. Shortly thereafter, Bacon got her license and signed on as an apprentice jockey with Pete Maxwell. Just like her husband. And she was off.

On June 5, at Finger Lakes, Mary Bacon tasted glory, riding her first winner, Cherlon, in her second race. By year’s end, she would finish in the money 160 times with 55 wins out of 396 races, earning $91,643 in purses. A highlight came on an August afternoon in Montreal, where Bacon went 5-for-5 in her mounts with three first-place finishes and two seconds. She was the leading apprentice jockey at Finger Lakes, and ended up ranked 23rd overall.

Advertisement

Maxwell’s three-year contract allowed Bacon the freedom to ride for other trainers, and her reputation quickly became that of a jockey who would race anyone, anywhere. Her days as Johnie’s housewife were probably numbered from the start, but once horse tracks were opened up to women, it took over her life. As she said more than once, “I’d rather muck out a stable than make a bed.”

Mary and Johnie’s relationship wasn’t built to last, and the pair split up in 1972. Five years later, Johnie would be killed in an auto accident.

Susan Bacon claims Mary never quite got over her first husband, even though the relationship had been a volatile one. “Mary tried to get Johnie back the entire time we were married, writing him letters and stuff, but a part of me still felt bad for her,” says Susan. “I know he was physically abusive to her because he was physically abusive to me.”

But in the summer of ‘69, things were good. Mary had a baby girl at home, prize money coming in, and plenty of mounts to be had. It was a banner year, up until she caught the attention of a local stable hand.

During her time as a celebrity, Mary often told the story of two harrowing attacks made against her by a crazed stalker, both of which she barely survived. The story goes like this.

Advertisement

Paul Corley Turner was a drifter. In 1969, he picked up work in the stables at Pocono Downs near Wilkes Barre, Penn., a track where Mary galloped horses. Turner would watch Bacon as he worked the stables, and before long he developed an obsession.

At 6:00 a.m. on October 14, Bacon’s agent, Roy Court, honked his horn outside her motel to let her know he was there to collect her for her morning workout. Versions of what happened next vary, but Turner was either in the backseat, or flagged them down and talked his way into a ride. Once in the car, Turner pulled out a knife, ordered Court to drive to some nearby woods, and locked him the trunk. Turner threw Bacon to the ground and put the knife to her throat.

In an August 1974 Genesis magazine profile, Bacon told writer John Veraga that Turner said he was going to disfigure and murder her, as he’d done to other women. She recalled those horrific moments, saying, “I remember thinking that it was too bad this was happening because I was booked to ride an excellent horse that evening. I did ride that night, and I did win, although I kept looking around for this nut, expecting to be shot somewhere around the quarter pole.”

Bacon managed to wriggle free and run away. Turner gave chase as she ran across railroad tracks and up a hilly embankment, gaining on her and then slipping (or, in another account, catching up to her until she kicked him in the shoulder and sent the knife flying), and she was able to reach Interstate 81 and flag down a passing motorist. Mary was unknown at that point, but her horrifying ordeal made the papers. In her first national exposure, the UPI story about Turner’s so-called “crush” ran under the headline: “Race Buff Tries to Bring Home Mary Bacon.”

Turner would later be picked up in Florida, but Bacon was off racing in Venezuela. Authorities couldn’t locate her and without her testimony, Turner was only sentenced to four months in prison.

Advertisement

But the horror didn’t end there. On May 25, 1971, after a day of racing, Bacon and her agent, Judy Wilson, returned to the Colony Motel near Churchill Downs. The bathroom light was on, so Mary grabbed a pair of scissors and booted open the door. Paul Corley Turner was inside the room, and he had a gun. He fired two shots. The first grazed Wilson’s face, the second hit her hand. (In later tellings, Mary said her leg was grazed as well.) Turner fled into the night.

It would take four months before Turner was caught. During that time, he called and taunted Mary with death threats. It’s said he even left a bullet on the hood of her car. According to Haney, Turner wrote Bacon a letter, asking for one in return addressed to “Earl Crook” in Chicago, which is where the FBI arrested him.

Charged on two counts, malicious shooting and wounding, and burglary, Turner was sentenced to 12 years in Frankfort, Kentucky. The second kidnapping received little newspaper coverage. Oddly, a UPI article on Bacon six months later mentioned both attacks in a single sentence about her perseverance, saying nothing would slow her down, not even “the time she was threatened with a gun.” The details of that horrific night all came out in profiles published a couple of years later, when Bacon was the hottest thing on four legs.

All true? Or just another wild tale meant to bolster the legend of Mary Bacon?

It seems that even at the time of the first attack, people doubted the veracity of Bacon’s story. Years later, she told White, “Everyone believed it was a PR stunt.” But a source close to Bacon’s family told Deadspin that the kidnapping story was absolutely true, and that Turner had even been seen lurking around Bacon’s house before it happened. Rowan also dismissed any notion that Bacon invented the first attack: “The idea it was staged in any way is 100 percent absolutely false. I saw her that night at the hospital and she was terrified, not just for herself, but for her entire family. ”

As for the second attempt on Bacon’s life, White was able to confirm the details of that incident in 1974. The FBI confirmed for her that Turner had been a wanted man, and the Franklin County Clerk confirmed that he had been tried and sentenced to 12 years in prison.As Bacon told White about the shooting, “We weren’t hurt seriously, but it was a helluva a way to prove to the cops my life really was in danger.”

Advertisement

There remained one person, however, who took issue with Bacon’s story. That person was Turner himself, who according to public records filed a libel lawsuit against a handful of publications, including womenSports, that had published Mary’s recounting of the attacks. Turner was still in prison when he filed the suit, which was thrown out. In 1981 it made its way to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals. There the lower court’s opinion was upheld, with the appeals court ruling that the articles in question were “substantially true” and that Turner was “libel proof.”

Public records indicate that a man with Paul Turner’s name and birth date died in Frankfort, Kentucky in 1999.

Those who knew Mary have said that Turner’s attacks left her with long-lasting trauma. Mary’s brother, Jim Steedman, told White that all of Bacon’s fibbing to reporters was done for the purpose of protecting herself and her family from Turner. In the lone interview Suzix Steedman gave following her sister’s death in 1991, she told horse racing writer Bill Finley that Turner continued writing Mary from prison and stalked her after his release, going so far as showing up along the rail at a Florida track.

“I think being kidnapped early in her career added a lot to her decision to be a cypher, or maybe just gave her a legitimate excuse,” says Neff. “Mary was different depending on who she was around and when and what was going on in her life. It’s interesting, the more one knows about her, the more they don’t.”

In April 1973, Bacon established herself in the New York racing scene, running at Belmont and Aqueduct, when the Gotham circuit was still prestigious. She also started racing for Jack Van Berg, the Hall-of-Fame trainer with more than 6,500 wins under his belt. Her first race day at Aqueduct didn’t amount to much, but it did draw spectators. Before her debut in the 10th race, the Times noted, “There were so many fans gathered around the paddock fence that one would have thought a stakes race was about to start.”

Bacon wouldn’t get her first Aqueduct win until the holidays, in part because she was sidelined for a good length of time by New York authorities following the Aegean Queen stable accident. (Naturally, she mounted up in other states.) On December 4, she galloped Buenos Aires to victory. The race paid $19.60 to win, and because he couldn’t help himself, Daily News writer Peter Coutros wrote: “Buenos Aires brought home the bacon for Mary.”

Advertisement

It was a heady time for the new track darling. By March of 1974, she had six wins and three places at Aqueduct, putting her in the top 10 riders at the track, alongside legends of the game like Angel Cordero Jr. Bacon supplanted her rival (and fellow fabulist) Robyn Smith as the top female jockey of the 50 or so in the country. Unlike Smith, Bacon never got the Sports Illustrated cover she desperately craved.

American newspapers, however, were taken with Bacon’s good looks, unbelievable backstory, and easily punable name. The inaugural edition of The National Star, which was Aussie publishing upstart Rupert Murdoch’s first American tabloid, featured a full-page spread of Mary decked out in resplendent white—turtleneck, leather belt, and knee-high leather boots. The National Star played all the sensationalist hits going back to her Oklahoma childhood, and included this out-of-nowhere declarative: “Some call her Legs and Bacon.”

Brands came calling, too. The perpetually peroxide-blonde Bacon signed with Revlon cosmetics to promote a new perfume named after the company’s founder. She was slated to be the original “Charlie girl,” the female spokesperson for the new perfume line aimed at empowered independent women. (Within three years, it would become the best-selling perfume in the world.) Fitting, because Mary always wore false eyelashes, lipstick, mascara, makeup, nail polish, hair ribbons, and gold hoop earrings while riding. That, and her trademark flowery underwear, worn under her see-through white nylon pants so that, as she quipped, “the boys back there have something to look at.”

Bacon wasn’t one to shy away from her sex appeal.Her photos in Playboy and its downscale hippie doppelganger, Genesis, were generally demur, more PG-13 than NC-17, but they certainly boosted her public profile. Yet Bacon never missed an opportunity to undermine her own status as a sex symbol. In Genesis: “I hate that sex baloney.” In the Boston Globe: “Sexual compatibility wears out so quickly.” In The Lady is a Jock: “For me, I don’t dig sex. I don’t get that much out of it… In the back of my mind is the pain I went through having a baby.” And in womenSports: “Who wants to see a naked jockey?”

Unfortunately for the pioneering female jockeys of the time, sex often intruded on their professional lives, which they were forced to live in a hostile and misogynist environment. The casting shed was industry standard. “If you don’t cooperate sexually, you don’t get the mounts—it’s that simple,” jockey Donna Hillman told the Times in 1976, further explaining that women who put out got better horses, and those who didn’t were left with “bums… impossible horses no one else would touch.”

Advertisement

Bacon echoed Hillman’s words while speaking to the Chicago Tribune, telling the paper, “Believe me, the closest way to a trainer’s heart is not through his stomach.” She addressed the topic again in Genesis, this time doing less to hide her anger at her circumstances: “Some people believe that every girl jockey sleeps with the owner she rides for. I know that’s not true… Everybody wants what they can’t have.”

Bacon’s sympathies didn’t extend to other marginalized groups, though. Disparaging gays was common practice. She told Haney that owners wanted to see a pretty little girl on a horse, not “some ugly dyke.” Later, in an interview with renowned Boston Globe fashion writer Marian Christy, Bacon offered up, apropos of who knows what, her thoughts on Billie Jean King. Bacon called her “half Woman of the Year,” and “butch.” In her womenSports cover story, Bacon had this question for White: “What woman reads about other women unless she’s queer?”

“Our advertising motto was ‘pound for pound, you’re as good as he is,’ and Mary Bacon was precisely the kind of person we were excited to talk about,” says Rosalie Pakenham, founding editor-in-chief of womenSports. “She was an arresting character because she was so complicated, tough and witty, a role model but not a goody two-shoes, a habitual provocateur. Mary was perfect for what we were trying to accomplish.”

Title IX came during the heart of the women’s liberation movement, but Bacon wasn’t down with that, either. She trashed “women’s libbers” and painted them as angry, man-hating types. Bacon was said to be friendly-ish with a few other female jockeys, but she took shots at “former model” Smyth for coming from money, unlike her rough-and-tumble, hillbilly self. Following the all-female “Boots and Bows Handicap” race in Atlantic City, Bacon hollered at Cheryl White, the only African-American jockey on the scene, accusing her of coming over on her horse. Mary wanted people to see her as a breed apart, a self-made rider traversing that lonely dirt road alone, so there was little in the way of solidarity.

“Mary was a good rider, a beautiful girl, and very popular with the fans, but even back when there wasn’t many of us, I never considered her a friend,” says Violet “Pinkie” Smith, the first licensed female jockey out of the Pacific Northwest. “She wanted to be on top of the world, the most recognized jockey, the movie star, per say.”

“Mary and I tolerated one another, but she wasn’t friendly. She didn’t really have any girlfriends. There was no sense of camaraderie with her,” Smith adds.

Advertisement

By the end of 1974, Bacon was fast becoming the celebrity she yearned to be. She joined the CBS broadcasting team for the $250,000 Belmont Invitational and got a rave review from Red Smith for her sportscasting skills. During the holiday season, she was pictured alongside such luminaries as Olympic swimming champion Mark Spitz, oddsmaker Jimmy “The Greek” Snyder, astronaut Walter Cunningham, economist Eliot Janeway, and writer Truman Capote in the “Gifts of Knowledge” catalogue from Houston’s Sakowitz Department Store. It was that year’s edition of the annual “Ultimate Gift,” and for a mere $5,750, some lucky cuss could’ve gotten a “Lessons in How to Be A Jockey” from Bacon herself.

“We had many inquiries and Mary was always very cordial in answering any questions,” says former CEO Robert Sakowitz. ”Unfortunately, her offering didn’t have a final takers.”

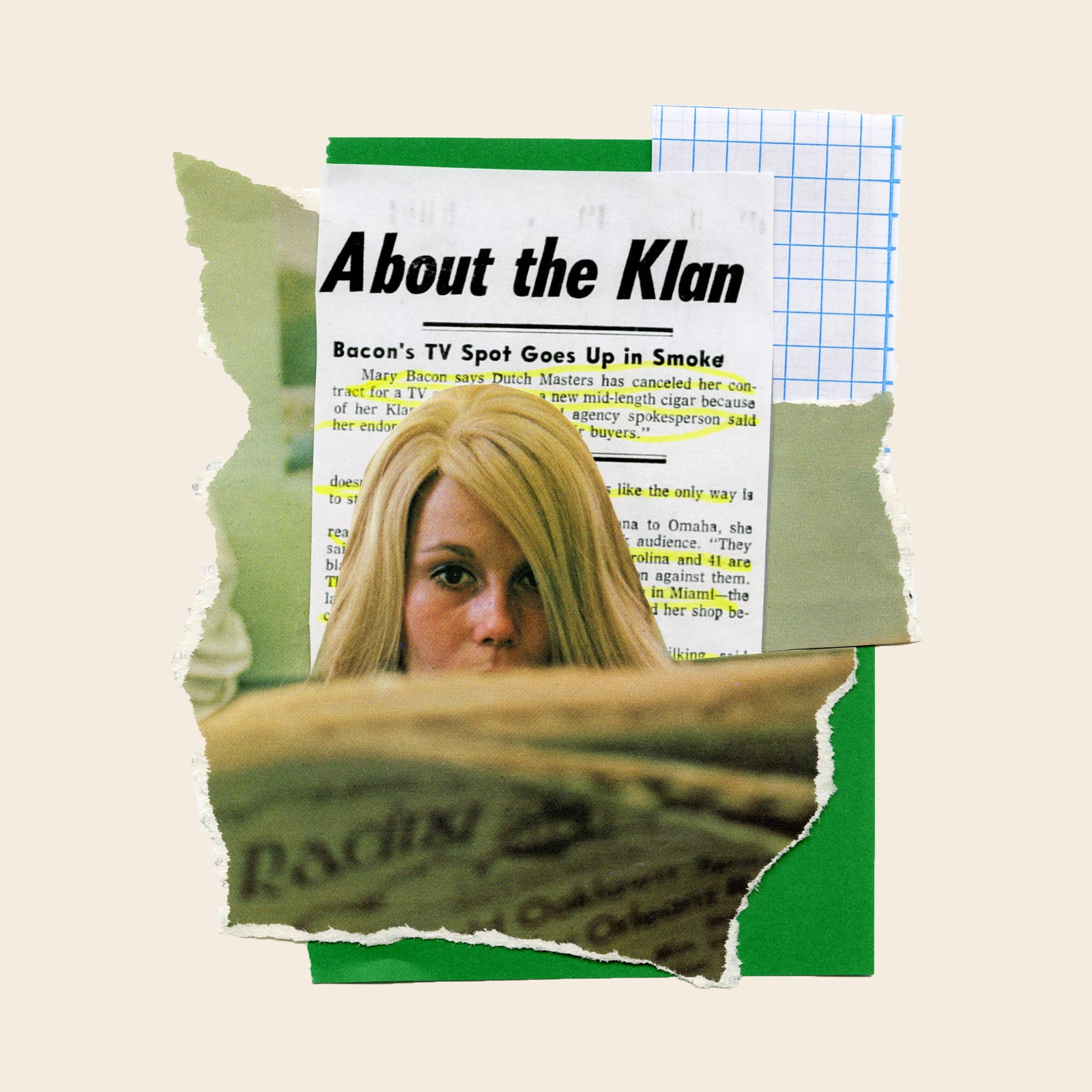

Mary Bacon got off to a strong start in 1975, leading Superstitious to victory by a nose at Pennsylvania’s Keystone Racetrack on January 4. When she headed down to New Orleans to ride for the Van Berg Stable in the winter, she had money in her silks. Bacon earned more than $20,000 racing in 1974 and considerably more in endorsements (more than six-figures by some accounts), and a movie about her life was in the works. She was even set to star in a television commercial for two new mid-length shapes of Dutch Masters cigars, the “Sprint” and the “Racer.”

While in the Big Easy, Bacon began running around with a recent Louisiana State graduate who’d made quite a name for himself by rabble-rousing on campus, but not as part of the typical anti-Vietnam uprisings that had been roiling up colleges for nearly a decade. This outspoken young man had an entirely different agenda. His civil unrest involved costuming himself in a Nazi SS uniform with a swastika armband, driving to Tulane, and picketing an appearance by civil rights lawyer William Kunstler with a “Communist Jew!” sign.

“I was visiting Mary and we were having dinner when this guy sits at our table. They start whispering, so I get up, sit at the bar, and ask if they know who he is. ‘Oh that’s Davey Duke, he’s trying to recruit people for the Klan,’” recalls Rowan. “I never got involved in Mary’s personal business, except for this one time. I said to her, ‘Do not have anything to do with this guy, he will ruin you.’ But the minute you say something like that to Mary…”

Advertisement

David Duke had recently founded the Louisiana-based Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, appointing himself Grand Wizard. Abandoning the overt Nazism he displayed as a college student, his plan was to present a kinder, gentler, clean-cut, non-hooded version of the Klan. To enter the mainstream, Duke wanted the Knights involved in the public sphere, in both politics and media. What he needed was bright, shiny Aryan faces to help deliver his message.

The 24-year-old didn’t have to look far. While his young wife was home pregnant with their first daughter, Bacon and Duke were gallivanting about town. Fair to say, the notorious womanizer got a lot more out of the fling than she did.

Duke announced a major Klan rally for April 4 1975, in the small town of Walker, Louisiana, about 20 miles east of Baton Rouge. Accounts differ on what exactly Mary knew going into the event, but it definitely wasn’t a typically secretive, backroom meet-up. The Grand Wizard promoted the hell out of it, even running a television announcement promising hot dogs, cold drinks, country music, and a special guest appearance from one of the country’s leading female jockeys. (A cross burning finale to boot!) Local television crews showed up to a festive scene comprised of 50 old-timers in white robes and hoods, with guns strapped to their sides, and an assemblage of young folk in khaki uniforms and shiny boots. In his fantastic book, Cross to Bear, celebrated Louisiana columnist John Maginnis cracked, “Only train wrecks attracted this kind of attention in Walker.”

“It wasn’t a coming out party for Duke, he was known locally, but it did put him on the map nationally,” says Tyler Bridges, author of The Rise of David Duke. “He was a force of nature that night. Duke solidified himself.”

After a few other speakers made their cases against race mixing and integration, Bacon stepped up to the mic. True to form, she was dressed to kill, sporting her best all-white getup, a black derby, and a beige trench coat. Bacon knew what the crowd of 2,700 rabid Klan supporters wanted to hear. Boy did she ever deliver.

“I organized the rally at the Old South Jamboree building and I remember Mary and her speech well,” says Bill Wilkinson, a former Imperial Wizard of the Knights of the KKK who now owns the Seven Seas Resort in Belize. “She didn’t mince words.”

Advertisement

Bacon exhorted the crowd, proclaiming:

We are not just a bunch of illiterate Southern nigger killers. We are good white Christian people, hard working people working for white America. When one of your wives or one of your sisters gets raped by a nigger, maybe you’ll get smart and join the Klan.

Even in a pre-cable television age, the fallout was swift. The damage Bacon did to her career was worse than all the broken bones, fractured vertebra, concussions, lung contusions, and blood clots on her brain combined. Revlon and Dutch Masters quickly dumped her. Her romp with the Grand Wizard didn’t survive the storm, either.

“David Duke is never concerned about the ramifications of his actions as long as they benefit him. That was one of the reasons I and several other of his original supporters quit him,” says Tom Metzger, a former KKK Grand Wizard, founder of the White Aryan Resistance (WAR), and rumored to be the inspiration for Stacy Keach’s character in American History X. “Mary was one of a long list of his victims.”

Steve Rowan and Susan Bacon swore up-and-down that Mary never expressed racist views or opinions. (The person close to the Bacon family said the same about Mary’s racial views, and claims Duke promised her higher-profile mounts, while also threatening to kill her family if she didn’t speak at the rally.) Separately, Rowan and Susan gave the exact same reasoning as to why Mary had decided to speak at Duke’s rally: for Mary, there was no such thing as bad publicity.

“The awful things she said at the KKK rally wasn’t who she was. Umpteen people have told me she wasn’t a racist, treated black people around the stables with respect, and was generous with bonuses after wins, which often wasn’t the case,” says Susan. “Her problem was she needed attention to breathe. Dumbest thing she ever did. Mary Bacon had it made…”

Advertisement

Presenting a phony face to bask in adulation wasn’t out of character, but Bacon didn’t exactly walk back any of the things she said at the rally, either. Within weeks, a Times article about the new energetic breed of “Klansladies” featured a racist New Orleans bookstore owner showing off a letter signed “K.K.K. Forever—M. Bacon.” She also gave a rambling nonsensical interview to the New York Post about how the only hope for the United States was for people to stick with their own kind, threw out both misleading crime stats and vague personal anecdotes, and professed, “I’m not into civil rights… I’m a Southerner.”

Mary was officially a pariah. One who was permanently branded by the Wall Street Journal with an unshakable epithet: The Klansman’s Jane Fonda.

If stumping for Duke and the KKK was a twisted PR stunt, it failed Bacon miserably. She headed to Hollywood Park in Los Angeles to resume her career, but her new KKK affiliation came with her. Worried about alienating fans of all stripes, owners shunned her, and she couldn’t get mounts.

In a baffling Los Angeles Times profile that was published in July 1975, Bacon was still claiming a destitute upbringing, while also saying she intentionally made up stories in the womenSports article to mess with Charlotte White’s head. She went on to say the KKK rally was a lark, something she was curious about after watching the movie The Klansman, and no different than the voodoo and witchcraft events she attended in New Orleans. Without acknowledging her own speech, Bacon said she joined the Klan but then found the whole thing boring, and that she should only be judged on her racing skills. For good measure, she claimed to be a “free spirit” while showing off a bird tattoo on her stomach.

Finally, in August, Bacon got a horse at Del Mar. She won her first race, on 23-1 longshot Cumpa in the fifth, paying a tidy $48.20. Still, there were plenty of people who didn’t want her there, along with a lone wannabe, white-sheeted knight.

Advertisement

“Mary showed up in San Diego and was being threatened all the time,” says Metzger. “I live not too far from the track so I contacted her, told her I would assign a couple of men to her for her safety but she declined. Then I lost track of her and didn’t hear anything more until she committed suicide. I will never forgive David Duke for what he did to Mary Bacon.”

Bacon had been the top female jockey going, but those days were rapidly fading.

“I came on the racing scene in 1980, and Bacon was already gone,” says Steven Crist, a longtime Daily Racing Form columnist and the author of multiple books on handicapping. “Being the first female to 100 wins has historical significance, but 281 total victories is nothing. The leading jockeys get more than that in a year.”

Crist also believes that despite the pro-KKK sentiments, Bacon could have continued if she had been good enough. “The racetrack has never been a particularly progressive place. It’s all about merit, and most of the people involved are to the right of Genghis Khan. There’s a huge libertarian streak in the sport. If a jockey’s good, it doesn’t matter who they sleep with or what they have to say. I know the story goes she couldn’t get mounts after the KKK appearance, but if she was winning daily races, she wouldn’t have been finished.”

To put Bacon’s career in perspective: She topped Robyn Smith, who hung up her silks with 247 wins, but was a thousand lengths behind Pinkie Smith, who triumphed in some 1,200 races. Compare that to legendary Hall-of-Famer Julie Krone, the first woman to win a Triple Crown race when she galloped 13-1 horse Colonial Affair to the 1993 Belmont Stakes crown, who hit the winner’s circle in 3,704 races, earning $90 million in the process.

Before fully crashing and burning, Bacon had one more glorious week in the sun. In November 1978, she spent a week as a Japanese media sensation. Piloting 12 horses at Tokyo’s Oi Racetrack, she brought in three champions, pocketed five million yen ($26,000 and change in American money), and increased the gate attendance by 30 percent. Strangely, the Stars and Stripes write-up of her time in Tokyo didn’t mention the KKK debacle, but did call her a “damn good jockey—and one hell of a woman.” The trip to Japan secured Bacon one final flower in her horse racing hat: she goes down in the Nipponese record books as the first woman to ride professionally in Japan.

Advertisement

After that trip, the sport of kings moved on from Mary Bacon, even if she hadn’t. She wouldn’t really make news again, outside a pair of near-death experiences. In 1979, at the defunct Cahokia Downs in East St. Louis, her mount flipped at the gate and landed on top of her. Three years later, at Golden Gate Park, she hit the track hard and ended up in a weeklong coma in Berkeley’s neurological intensive care unit. She had swelling on the brain and floated in-and-out of consciousness. At the time, her second husband, Jeff Anderson, called it miraculous she didn’t have any fractured bones, only a “broken brain.” Anderson illustrated the point by noting cops would pull Mary over for drunk driving when she was completely sober.

“I was in the race at Golden Gate Park when Mary went down. She wasn’t moving. We all knew when the ambulance carted her off it was serious,” says Pinkie Smith. “She showed up a few months later and the damage was obvious. She sat on the bed, talking to us, but it was clear she was not the same old Mary. Funny thing is, on that day, she was friendlier to me than she’d ever been.”

Even after everything she’d done to destroy her own career, and everything horse racing had done to destroy her, Mary Bacon should have ridden off into the sunset financially secure. She sued Cahokia Downs, alleging the starting gate crew was negligent, and won a $3 million judgment. The track declared bankruptcy in September 1979, and Bacon said she never saw a dime. A document obtained by Deadspin indicates that though it wasn’t the full judgment, Bacon was potentially in line to receive a significant sum. (In a wild 2018 conspiracy theory-laden Facebook post, Rowan says Bacon had a “substantial amount of money” at the time of her death.)

There was even a chance for Mary to find her way back into the world of celebrity. The movie about her life that had been in development pre-Klan rally went by the wayside, but two Hollywood veterans remained interested, acquired her life rights, and worked with Mary to try and bring her story to the multiplex. Television producer Mark Zaslove and actress Mary-Louise Weller, best remembered as Mandy Pepperidge, the object of Bluto Blutarsky’s Peeping Tommery in Animal House, took meetings with Bacon, wrote a warts-and-all screenplay, and even toyed with casting Mary herself.

“The Mary Bacon project started as sort of a sexy horse racing Raging Bull kind of thing, an imperfect character focused on one thing as their world crumbles around them,” says Zaslove. “The idea was fine, and the script was solid, but dealing with Mary really became a chore. It wasn’t much fun, all the crap she’d stirred up.”

Advertisement

Weller and Zaslove had put in a lot of work, though, so they kept the story alive, if on life support.

“After her suicide, Mark and I decided her life was actually a black comedy and rewrote it that way, but it didn’t go anywhere,” says Weller, who retired from the movie business for a second career in the equestrian world.

Bacon’s last major magazine cover came in 1977, a cheesy shot on the cover of the U.K. publication Titbits showing off her bird tattoo. After her Golden Gate accident, Bacon dropped off the racing circuit and tried to live a regular married life. It didn’t take. At some point, she began beating the bushes, particularly in Texas where parimutuel betting was new. She easily found a quack to get her a license. Her final mount came at Bandera Downs in Texas in 1990. The following spring, the once-feisty Mary Bacon was barely sentient.

“Mary never gave me the time of day until a couple of months before she died,” says Susan Bacon. “I was working in the grandstands at Oaklawn in Arkansas, she was a shell of what she had been, a horse racing queen. I told Mary, ‘my daughter adores you.’ She straightened up her back and sat up, because it’s what she always wanted, attention and adulation.”

The morning of June 7, 1991, on the eve of the Belmont Stakes (in which, atop Subordinated Debt, Julie Krone became the first female jockey to race that leg of the Triple Crown) Mary Bacon sat in a shabby motel room in Fort Worth, Texas. She just up and split, leaving a note with Anderson that she was going to Texas, but providing no other details. At this point she was suffering from cervical cancer, which had taken her mother’s life just months previous, but those I spoke to say Mary’s diagnosis wasn’t fatal. What got her was not being able to get through a morning gallop without debilitating pain.

Advertisement

Bacon was 43 years old. Her racing career had left her with more than 40 broken bones, numerous hospital stays, and horrendous, compounding physical deterioration. It was, perversely, exactly where Bacon always thought she’d end up. Way back in 1973, on the night she had been honored by Philadelphia sportswriters for her toughness and courage, Bacon confided in Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Bill Lyon:

I only feel completely free, completely myself, when I’m on a horse. My whole life exists from the gate to the wire.

You can feed a horse and take care of him and he’ll run his heart out for you. You can do the same for a person, and he’ll knife you the first shot he gets.

I do know this about myself—I use horses to block bad things out of my mind. But listen I can’t do anything else. I can’t even cook. I don’t want to. All I want to do is ride… ‘til I’m crippled or I’m dead.

For as much as Bacon’s life story is tangled up in myth and exaggeration, it’s hard not to feel a deep sincerity emanating from those words. Nobody may have ever really known who the real Mary Bacon was, but the one piece of her story that is undeniably true is that she loved to ride. What else but love could have compelled her, after all the pain and trauma racing had brought to her life, to continue saddling up and trotting into the gate?

By the time she found herself in that motel room, though, Bacon had run out of mounts. Using a right arm that had been fractured in three different places, she raised a .22 caliber pistol to her temple and pulled the trigger.

All collage photos via womenSports, Newsweek, Genesis, and Playboy.

Patrick Sauer is a freelancer for a lot of spots. Follow him on Twitter, if you please.