Last year U.S. ArmyChief Warrant Officer Charles Overby set out to legally import his 1985 Land Rover Defender from his station in Germany to the U.S. Now the truck’s trapped at an impound lot, and could potentially set a whole new precedent for automotive importing because of one arbitrary discrepancy.

If you want to import a car from a foreign country that wasn’t intended for American consumption, there are a few basic rules most people can’t get around: the vehicle must be 25 years old or older to be exempt from regular import restrictions (up to and including crash testing), and it must be 21 years old or older to be exempt from emissions testing.

So why would the Environmental Protection Agency care about one 31-year-old Defender?

Advertisement

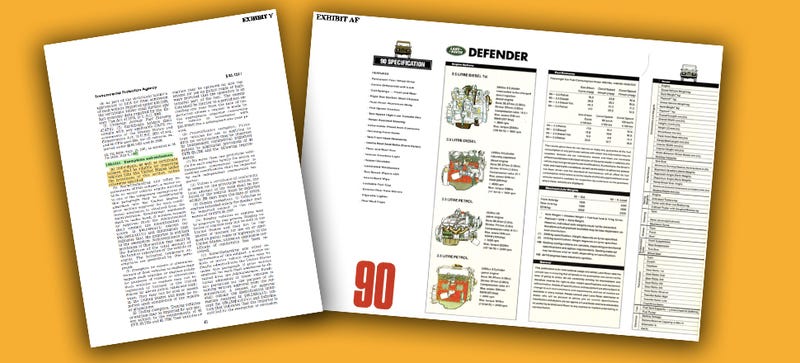

It’s because this particular Defender showed up on our shores with an engine it wasn’t built with. Overby’s ’85 Defender left the Solihull, England factory with a 2.5-liter diesel engine; at some point in the truck’s long life, it was swapped for a 2.5-liter turbodiesel engine from 1991.

Given that the new engine is old enough to import, the car sounds like a no-brainer. But the Environmental Protection Agency takes issue here.

Sponsored

Deep in their stacks of stipulations for how a car can be imported or registered for road use here in the U.S. is a line that says cars coming in without their original engine can’t come in at all, according to Overby and his attorney. That is, unless certain criteria are satisfied.

Now this case is about to go before the Court Of International Trade in New York City, and the outcome could lay down precedents for the importing of engine-swapped cars. Federal officials were not able to comment, but we spoke at length with this Land Rover’s owner and his representative.

The War On Old Land Rovers

Like the Nissan Skyline and original Mini Cooper, the Land Rover Defender—a trucklike vehicle built for safaris and farm work—is both a popular car to import and a common target for federal authorities.

In the summer of 2014, federal law enforcement officials conducted a series of early morning raids to confiscate 40 vintage Land Rovers from ordinary citizens. Federal prosecutors suspected the trucks were brought to the U.S. illegally by importer Aaron Richardet; in seizing the cars, they were reportedly building a case against him. Agents effectively “arrested” the vehicles, which law enforcement can do thanks to civil forfeiture.

Advertisement

Almost a year later, the trucks were returned to their owners, and the case against Richardet was dropped.

That result was due in large part to the efforts of North Carolina attorney Will Hedrick; a Land Rover-loving lawyer who was made aware of the vintage Defender mass-confiscation via online forums and stepped up to represent their owners pro bono. Hedrick’s case against the government succeeded in getting all the seized trucks returned to their owners.

Naturally, Hedrick is now a bit of a legend in Land Rover fan circles, which is why Overby reached out when the EPA refused to let his 31-year-old Defender 110 through customs—after it’d been shipped here all the way from Europe, at the expense of the United States Army.

A Man And His Rover

Overby is an active-duty officer in the U.S. Army. While stationed in Europe he bought himself a longbody Defender for the same reasons anyone else does: they’re fantastic adventure vehicles, old-school trucks capable of conquering the wilderness in ways few others can.

But the Defender is not known for its reliability, especially when they’re almost old enough to run for president. It probably won’t shock anyone to read that at some point during the truck’s long life, its 2.5-liter diesel engine went kaput and was swapped out for a newer one. The replacement was another 2.5-liter Rover diesel, but with a turbo. This engine is known as the 200Tdi.

Land Rover introduced the 200Tdi in the Defender 110 in 1989. Overby told me that the swap is from a 1991 truck.

But since the vehicle remained architecturally identical through all those years, the engine is a direct drop-in replacement. In fact, Overby explained that it’s pretty commonly performed on the earlier vehicles.

With the truck running well—or as well as a Thatcher-era Land Rover ever does—Overby was enjoying the good life greenlaning with his family in the sweet rig his young son had named “Alice the Zombie Slayer.”

Coming To America

Then in the summer of 2015, Overby said he was given new orders, and he and his family relocated to the United States. Naturally he wanted to bring the Rover too because while it’s a decent work truck in Europe, it’s a rare and coveted collectable on this side of the Atlantic.

As part of his reassignment deal with the military, Overby said the Army paid moving costs up to a certain amount, which included the transportation of privately owned vehicles (POVs.)

An outfit called International Auto Logistics was selected to picked up the Land Rover in Ansbach, Germany and lug it all the way to Charleston, South Carolina, which Overby said went off without a hitch.

When you’re trying to bring a foreign car into the United States, there’s a big stack of forms to flip through and boxes to tick. One of them is from the EPA, and if you’re working with a vehicle as old as Overby’s you get to check “Code E,” which, according to the agency, means:

“A vehicle at least 21 years old (calendar year of manufacture subtracted from year of importation) and in original unmodified configuration is either exempted or excluded from EPA emission requirements, depending on age.

Vehicles at least 21 years old with replacement engines are not eligible for this exemption unless they contain equivalent or newer EPA certified engines. Customs may require proof of vehicle age.”

2016 began and Overby’s Rover was safely sitting in a parking lot at the Charleston port. The Department Of Transportation was ready to welcome it to our roads with open arms and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration had no issue with truck being naturalized, Hedrick told me.

But as the U.S. Customs and Border Protection team went through it, they decided they weren’t too sure about this “Code E”, business and with a call to the EPA, the truck was imprisoned at the port.

The EPA’s issue

A close read of “Code E” reveals what went wrong: that bit about “original unmodified configuration.”

Thanks to the engine swap, the “original” clause no longer applicable. And so the EPA said “good day, sir” and shut Overby down.

What might be the most frustrating fact here is that the newer engine is 25 years old, and would be perfectly legal to import if only the whole truck it belonged to were coming in too—to say nothing of the fact that the replacement engine is likely less polluting than the original.

In other words, the EPA is vetoing an engine-swapped vehicle on a technicality, even though both car and engine would be eligible to import on their own.

Overby, hoping logic would prevail, brought the issue to his local congressman, South Carolina Rep. Mick Mulvaney. Mulvaney’s office passed the complaint up to EPA Assistant Administrator Cynthia Giles, and while they haven’t achieved the resolution Overby’s looking for yet, they did manage to get a response.

Giles maintained the EPA’s decision to keep the truck out of the U.S. She cited the “original equipment” language as a condition of the 21-year exemption. She went on to explain that exceptions could only be issued if the vehicle was specifically granted a “Certificate Of Conformity” by the EPA and/or imported by “Certificate Holder” in the letter she sent in reply to Congressman Mulvaney.

And Giles wrote that only automakers and registered companies “that specialize in converting uncertified vehicles to meet the EPA’s requirements” could be “Certificate Holders.” Since Overby is neither, he’s out of luck.

As far as the EPA is concerned, Overby can abandon the truck where it sits for the U.S. government to crush or put it on a ship to “anywhere but here.” Meanwhile, it’s racking up parking fees at $10 a day while its tires go flat and sea birds defecate on its paint.

The Defense

This is where Hedrick comes in. Since the Land Rover case last year, he’s started specializing the laws surrounding vehicle imports, with particular interest in off-road vehicles from England. He’s currently representing Charles Overby.

As far as Hedrick’s concerned, the truck’s old enough to be here. And the engine’s old enough to be here. But the key argument in allowing Overby’s Rover in is the fact that it effectively is an unmodified age-exempt vehicle.

The 1991 Defender 110 was essentially the same as Overby’s ’85, so putting a ’91 200Tdi engine in the truck should only make it a ’91 model in the eyes of the EPA, which should be legal to import.

Now, a key difference between Overby’s case and the dozens of Land Rovers that were taken in 2014 is that the truck we’re talking about now wasn’t seized, it was simply “denied entry.”

“If they had seized it, we could have taken the matter to a U.S. District Court right away,” Hedrick explained to me over the phone, “but in this case we are limited to the court of international trade.”

That basically means Overby’s options for restitution are more limited.

Hedrick thinks that while the situation may end up in a court setting, the EPA will do everything it can to settle the matter before a judge can hand down a ruling. If that were to happen, the EPA would effectively be handing over control of the interpretation of their rules to someone else. Not a good look for them.

“This regulation has never been tested in court, which is why i think the EPA wants to settle and also why it was denied entry [rather than seized],” Hedrick said.

The stakes are high because there’s potential for precedent. Once the EPA okays Overby’s engine swap they’ll have to allow others. And why shouldn’t they? If a vehicle is imported in a completely legal configuration, the fact that the dates on the engine and sheetmetal don’t match seems like a ridiculous reason to keep cars out.

But as Hedrick explained to me, this should be a really easy case for everybody to walk away happy from. Overby’s Land Rover and its engine are not only both old enough to satisfy the EPA’s requirements, but the engine and vehicle combination is identical to a configuration of the truck that would be legally importable were it not for the fact that it was assembled over a few extra years.

It seems all the EPA would have to do to maintain the status quo would be to clarify their regulation, stating that vehicles with engines outside a standard configuration would remain beholden to the agency’s right of refusal.

The Fight Continues

Hedrick explained to me that he filed a formal petition to the U.S. Customs and Border Protection office at the port of Charleston in February, and that the agency had 30 working days to respond.

That deadline came and went, and last week he found out what the agency’s first response was. Or lack-thereof.

“They did not respond, and in failing to respond, the default under CBP regulation is to rule our protest denied,” Hedrick said in an e-mail. That doesn’t mean he’s giving up, but the situation he laid out is enough to make any would-be importer want to eat a stress ball:

“In truth, I do not think it was ever genuinely considered. To paint a picture for you, I had to file the protest in quadruplicate (4 copies x 100+ pages). When I spoke with the CBP officer in Charleston today I asked her who had received each of the four copies. Her answer: only her. One was reported to be on her desk, while the other three were reported to be in a file in her drawer.

When I asked her whether she had provided a copy to the EPA, the response I received was ‘no.’ She went on to state that they ‘couldn’t respond in 30-days anyway,’ and that ‘only people who want to take their issues to court request for expedited 30-day review.’”

At this point Hedrick does not think that the CBP gave his protest any attention, and apparently the EPA may not have even been aware that it was filed.

Now, Hedrick will bring the case before the Court Of International Trade with a formal protest to get that ratty old truck onto American roads.

Hedrick, once again, is representing the Land Rover owner for free. Overby emphasized how grateful he was for this to me. “I would have no recourse without Will,” he told me.

And this is what normally happens to hapless “importers” of relatively low-value vehicles. Once the government says no, it quickly becomes too expensive for the average person to litigate or arbitrate the issue.

As frustrating as the lack of a truck obviously is, Overby said he is more bothered by the principle of the situation. He said he thinks it’s ridiculous that the government is refusing to realize that the truck does in fact satisfy their entry requirements, simply because it fails an arbitrary boilerplate mandate to be “unmodified.”

We’ll keep you apprised of what the result is, and what this will mean for everybody else who wants to import a car in the future.