Racing is sort of like an evolutionary crucible for cars. The specific challenges and criteria of a given type of racing will invariably breed cars uniquely adapted to those particular circumstances. When racing officials and overseeing bodies impose rules and restrictions, it’s fascinating to see how the cars evolve to incorporate, or maybe more likely, overcome those restrictions. Sometimes the results are beautiful machines, bred for one specific purpose, and sometimes the results are absolute freaks. I want to tell you about some freaks today. The specific freaks are the Lion-Peugeot long-stroke Grand Prix racing cars of the early 20th century.

There’s a lot of stuff in the metaphorical trunk of the phrase “Lion-Peugeot long-stroke Grand Prix racing cars” to unpack, so let’s start at the beginning. We’re all familiar with the old and venerable French automaker Peugeot, so what’s up with this “Lion-Peugeot” business? Is that just Peugeot?

Not exactly. Lion-Peugeot was born from in-fighting within the Peugeot family, which is actually kind of complicated and confusing. It seems the original Peugeot company, a metalworking firm known (and still known) for their coffee grinders and bicycles, branched out into cars in 1890, but disagreements in the company between cousins Eugène and Armand Peugeot about how much to invest in automobiles caused a split in 1896, when Armand Peugeot started Automobiles Peugeot, separate from the original Peugeot.

Now, in 1905, the Peugeot company was run by Eugène’s sons, Robert, Pierre, and Jules, and they decided to reconcile with Armand, who permitted the original Peugeot company to get back into the car business, building automobiles under the name “Lion-Peugeot” starting in 1906.

Advertisement

Got all that? Good. Even if you didn’t, don’t worry, the companies merged back together in 1910, so for most purposes you need only concern yourself with the existence of one Peugeot.

But right now isn’t one of those circumstances, because we’re talking about some very odd race cars built by Lion-Peugeot, though to be fair, they come from 1910 and on, after the companies re-joined, but were still building cars under the Lion-Peugeot name. Easy, right?

Advertisement

These were race cars built to compete in the Voiturette Grand Prix class, a class designed for small cars with relatively small engines. The way the rules were set up was designed to favor single-cylinder engines, and there were strict restrictions on how much area a piston could take up, in effect rules limiting the cylinder’s bore, which is its diameter.

Advertisement

There were no rules limiting the stroke of a piston, though, meaning how tall a cylinder was, and how far a piston in that cylinder would travel. Generally, when building engines, you don’t really want to have a crazy ratio between bore and stroke, since engines with much more stroke than bore (known as undersquare) have pistons that move much more in the cylinder and move faster, which causes stress on the crankshaft, though they do hit peak torque at lower RPMs, and there’s many modern undersquare engines that work just great.

Advertisement

But they’re not engines like these old Lion-Peugeots. To get more power, the Lion-Peugeot engineers wanted more displacement, and if they couldn’t make the cylinder diameters bigger, the only way to go was, well, up. They designed incredibly long-stroke engines, coming up with cylinders that looked like stove pipes, with engines like a 3.5-liter V4 that had a bore of 65mm (2.56 inches) and a stroke of 260mm (10.24 inches).

Those cylinders had the proportions of a baguette, and they made for very strange-looking engines. To compare with another V4 engine, take the Ford Taunus V4, which, in 1.7 liter form, had cylinders with a bore of 90mm (3.54 inches) and a stroke of 66.8mm (2.63 inches). That’s what you’d call oversquare (bore larger than stroke) and is much more in line with how engines are normally built.

Advertisement

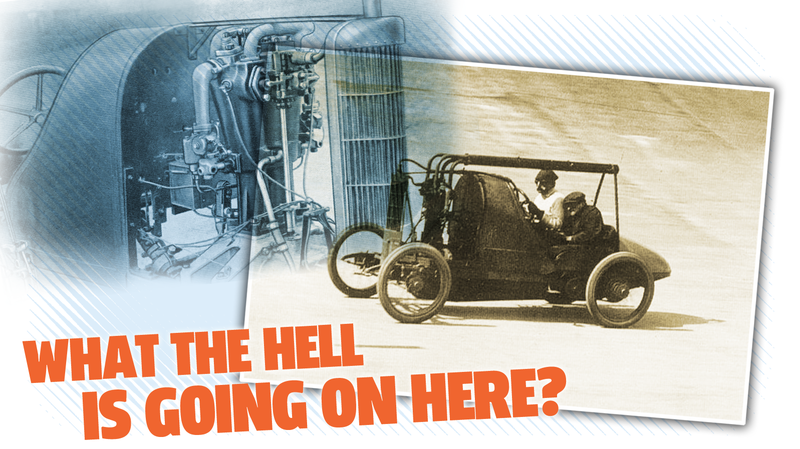

Also strange was that these engines had six valves somehow crammed onto their tiny heads—three intake and three exhaust. The resulting engines were insanely tall and narrow contraptions, with radiators that looked like deco skyscrapers and really weird exhaust setups like this one:

Advertisement

Just look at that thing; the engine is so tall they decided, screw it, let’s just run the exhaust right over the driver’s head there. Just cram that scalding-hot pipe of noxious gases right by the driver’s tender face and scalp.

Man, everything about that picture! Look at that radiator! It’s like an office tower. And that engine—in this picture, I think it’s a V-twin version—looks like the creepy castle some dark wizard would inhabit in a fantasy novel.

Advertisement

Here’s another one of these cars, with a somewhat less alarming exhaust setup, but the same insane proportions. Visibility must have been pretty awful in these things, at least straight ahead. I imagine drivers looked around the sides of the hood a lot.

Advertisement

These Lion-Peugot weirdos actually did pretty well. The long-stroke engines made around 40 horsepower, pretty good for that era and racing class, and they racked up a good number of victories in the 1910 season.

Advertisement

The Lion-Peugeots, especially the V4 versions, weren’t really the most stable of race cars, and soon other cars were beating them, and by 1911 the rules had caught up to these bonkers machines, limiting overall capacity to three liters and mandating that bore to stroke ratios had to fall within 1:1 to 2:1.

So, that was pretty much it for these deeply strange and freakish cars and engines. The development of these cars was an absolute technological dead end, as there’s no really good reason to design cars like this outside of the wildly specific regulatory world of early 1900s Voiturette-class Grand Prix racing.

Advertisement

That’s what makes these cars so fascinating—they’re entirely a product of a very specific era, situation, and arbitrary set of restrictions.

It’s easy to be frustrated by racing rules and restrictions, but the truth is the quest to work with and around them are what makes crazy, creative, and exciting race cars possible.