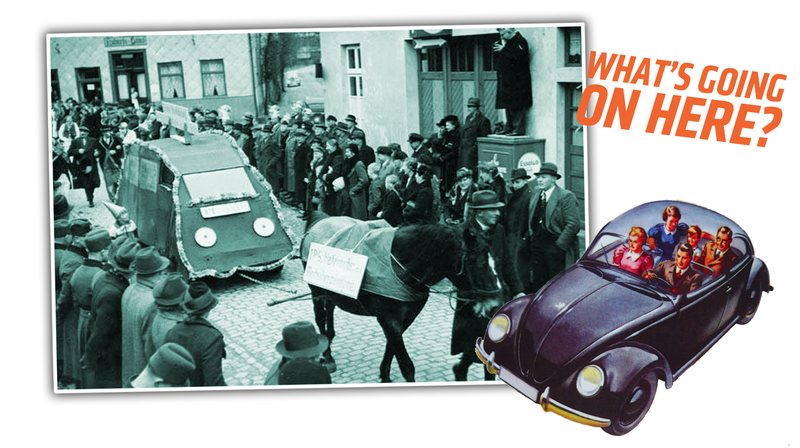

As an unapologetic Volkswagen obsessive, I feel like I’ve seen almost every old, archival photo of the prehistory of the iconic Beetle, even the disturbing and difficult ones from the car’s birth under the Third Reich. Of course, I haven’t seen everything, and occasionally I’ll encounter a truly unexpected photo that shows something quite weird and confusing, like these two photos of a Volkswagen effigy in what might be either a parade or protest from 1939.

So, what exactly is going on here? What are they either protesting, or maybe celebrating? To try and figure this out, a little history is in order.

Advertisement

First, I was told this photo was taken in February 1939, during the Berlin Motor Show. This motor show was significant as it was the first real public introduction of a car called the KdF-Wagen, which was the German acronym for Strength-through-Joy.

The creepily-named Strength-through-Joy organization was Nazi Germany’s state-run leisure organization. This was one of those very Nazi ideas where things like vacations and cruises would be run by a governmental agency, which you would think would suck the fun out of pretty much everything in favor of setting up scenes of blonde people cavorting in verdant fields.

Advertisement

The KdF organization also became the means by which the German people would be able to get one of Ferdinand Porsche’s “people’s cars” via a scheme involving buying saving stamps in a little booklet. The car we’d later come to know as the Volkswagen Beetle started life as the KdF-Wagen, and the only way to buy one was via these books of savings stamps.

Here’s the thing, though: it was all kind of a scam. Funds were misallocated, too much money was spent on building the big factory at Wolfsburg (known then as Stadt des KdF-Wagens bei Fallersleben, or City of the KdF Car at Fallersleben), and very soon that factory would switch entirely to production of KdF-based wartime vehicles like the Kubelwagen, and no civilian cars were ever built for the people who had saved their money and filled their little stamp books.

Advertisement

There is, of course, much more to this story, but that gives us the key facts we need to try and make some sense of these images.

There’s very little information about these pictures. According to the excellent Volkswagen Prototypes Facebook group, this is what’s going on here:

“Meanwhile impatient customers of the new Volkswagen had organised a street parade sometime in February 1939. The horse is pulling what appears to be a mock-up of the VW.”

Advertisement

The presumably canvas-and-paint KdF-Wagen-like “costume” is draped over a car, which is being pulled by a horse. There’s only one sign that has legible words here, and it seems to translate to something like “first taste” or maybe “first presntation of the KDF Wagens in Amte Vechta.”

This is sort of confusing, because Amte Vechta is nowhere near Berlin and the motor show, where you would think such a whatever this is would have been most effective.

Advertisement

The description called it a “street parade” but since it’s being done by impatient potential KdF buyers waiting for their cars, could this more accurately be considered a protest? Were people angry that nobody had gotten the cars they’d paid for, and were doing this to draw attention and increase pressure on the KdF?

I asked the historian who runs the Volkswagen Prototypes group about this, and here’s what he told me:

“I wonder if this can even be called a protest, more a tongue-in-cheek stab at the length of time it was taking for the VW project.”

Advertisement

The hesitancy to consider this a protest is sensible, since Nazi Germany was notoriously harsh on protests of any kind. The only really notable protest that had any sort of impact in Nazi Germany was likely the Rosenstrasse Demonstration in 1943, and that was for something far more serious than not getting a car.

The Rosenstrasse Demonstration was a demonstration by, primarily, non-Jewish wives of Jewish men who had been taken captive and held in Berlin, prior to their likely shipment to concentration camps. The protest happened just after the German defeat at Stalingrad, and the Germans were not eager to sow more unrest and uncertainty among the population, which worked to the protester’s advantage.

Eventually, the protest was mostly successful, with the 200 or so protesters keeping enough pressure on the Nazis to get the attention of the international press, and to get the Nazis nervous about greater unrest. Of the 2,000 Jewish men held there, all but 25 were eventually released.

Advertisement

That’s a very unusual example of not just a protest in Nazi Germany, but one that actually had real results. Is it likely as early as 1939 German citizens would have been pissed enough about not getting their cars to stage a protest that could potentially embarrass one of Hitler’s pet projects? I’m not sure about that at all.

It’s possible the protest was planned and organized by the KdF or some KdF-related agency as a sort of publicity stunt to show how eager people were to get their cars. It’s a pretty devious and calculated move if this is the case.

Advertisement

That is, if that’s what was happening here at all. Which, I’ve just now found, it isn’t. At all. But the story is still quite strange.

The images of the KdF effigy are actually from something called the Dammer Carnival, a festival in the city of Damme, which is in the district of Vechta, Lower Saxony, the place referenced on the sign in the picture. The pictures seem to be from the 1939 Dammer Carnival, which included a parade with such groups and floats as

“ a 37th Infantry Regiment music corps, flag, and two prince carriages. The topics were very local in nature, including time-typical defamation such as the “Exodus of the Jews and their last belongings”, the KdF car and a group of RAD men.”

Advertisement

So this fake Ur-Volkswagen was a somewhat satirical entry in a parade that also included such other Nazi-era knee-slappers as the “exodus of the Jews and their belongings.” Yeesh.

Also interesting is this tidbit about the carnival’s honorees:

This year, the prince came from the known environment with Theodor Koch, especially as he chose Karl Koch and Josef Klostermann as adjutant and Heinz Nordhoff as court jester.

Advertisement

That’s notable for the court jester, Heinz Nordhoff. If this is in fact the same person, Heinz Nordhoff was the person chosen by the British to re-start the Wolfsburg Volkswagen factory after the war. Under British rule and Heinz Nordhoff’s management, the factory began to produce cars again, and Nordhoff was largely the person responsible for transitioning the factory into what became modern Volkswagen.

That’s a pretty strange coincidence and real-world foreshadowing: the Carnival that Nordhoff was jester for was the one that featured a satirical KdF-Wagen float complaining about lack of car production, the very thing Nordhoff would be accomplishing after the war.

Advertisement

I’m still not exactly certain just how satirical or sharp the KdF parade float-gag actually was. Was this a real point of contention, and was it an actual jab against the Nazi-run KdF, and they were able to get away with it because of the cover of the Carnival and it’s history?

Or was it just a softball thinly-veiled promo to drum up KdF-Wagen orders (that would never be fulfilled) on behalf of the Kdf?

I have no idea. This strange picture ended up telling a far more unexpected story than I imagined, though, so that’s something at least.