Twelve hours in, I lost the last scraps of sanity.

Pinned by a vise-tight five-way seat belt, I rode a steel cage through a barrage of noise and light, sucking down air tainted with aluminum and motor oil.

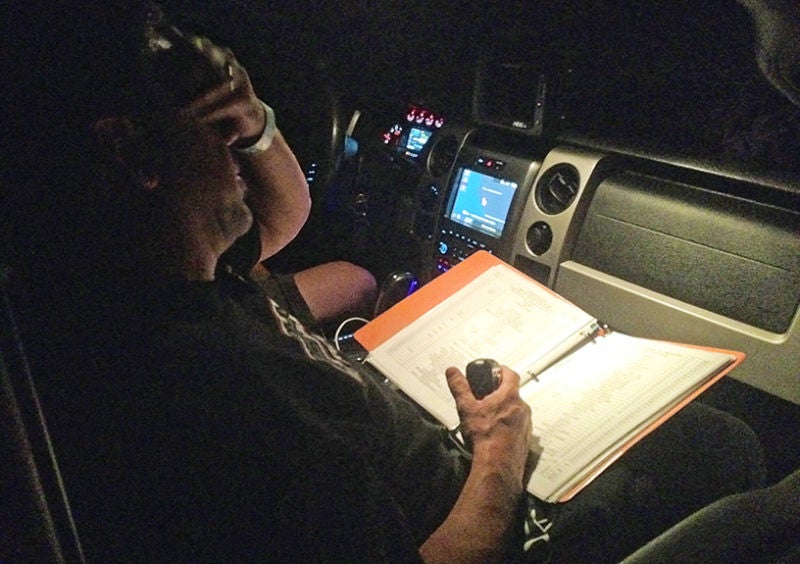

I was riding shotgun in a tiny beast of a truck, plowing through the Mexican desert in a sadomasochistic speed contest called the Baja 1000, fighting exhaustion and madness and sadness as I called directions to my driver, Ron Stobaugh.

Advertisement

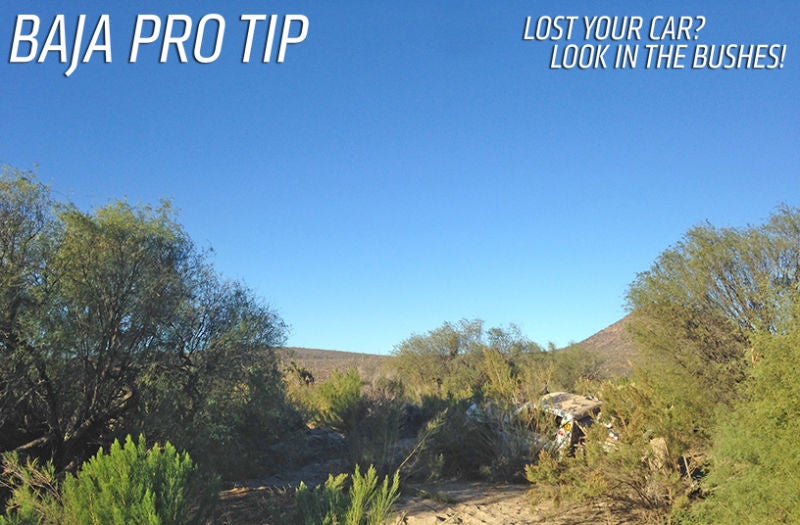

You know how a bush or a cloud might look like a car or cow from far away? It’s like that, but the bush is a car. There’s no question in your mind. Why’s there an Acura NSX out here in the desert? There wasn’t, of course. It was a wedge-shaped rock. But I couldn’t work that out until it was spitting distance from our bumpers.

There was no choice but to acknowledge the gaps in my lucidity; I started giving Stobaugh fewer directions. We were in daylight, so it was easier for him to see than it had been in the pitch-black we started our hellride in, but the chance of me fatally confusing “left” from “right” had become alarmingly high. I stuck to calling out clearly-marked dangers and triple-checking the biggest turns.

Sponsored

We had already crashed three times. I saw our fourth crash coming 500 meters away, but didn’t have the wherewithal to warn my driver. I could barely keep my eyes open. We paused at the top of a ridge surveying a long, treacherously soft-looking wash section; basically a river of sand where there used to be water. The map had it creatively labeled “SOFT WASH.”

Stobaugh is an excellent driver, but no one is infallible. He charged into the wash on a sloppy half-assed angle. The car came to rest at about a 40 degree starboard list in a prickly pile of cacti.

He shut the engine off without trying to reverse. We both knew it was hopeless. I knew it because he didn’t say a word. He knew it because I didn’t say anything either.

For an hour that probably only really took a minute, we just sat there staring straight ahead into the hot nothing we’d elected to spend a day racing through. What the fuck were we thinking?

There was no bravery or sense left in the cab of that race car. Just two husks, breathing.

840 Miles in 33 Hours, or Bust

For monied foreign assholes, Mexico’s large western peninsula is known for two things: spring break and off-road racing, which is basically spring break for rich rednecks slightly more interested in getting an adrenaline rush than getting drunk. (That usually still happens too.)

The guys and girls who go desert racing are generally well-humored and well-funded by day jobs in unrelated industries. Out of 200-odd competitors in a race, there might be a handful of “professionals” with big sponsorships and a lifelong background of involvement with motorsports. The rest are hobbyists, friends, fierce competitors but fun-havers first.

This group of folks actually has a name; “Southern California Off Road Enthusiasts” generally referred to as SCORE International. A SCORE race can be anywhere from 200-something to 1,000 miles long. People can show up in cars, trucks, buggies and motorcycles.

When the green flag flies, they follow a GPS line over terrain that ranges from paved highways to dirt roads to sandy cacti forests to goat paths to rock scrambles, with a million opportunities to wipe out or wash out every mile.

SCORE’s main multi-race series in Mexico is called the World Desert Championship. And the Baja 1000, held every year in November, is basically their Super Bowl. For 2015 it was a loop of 840 miles—from Ensenada into the wild sandy abyss and back again—in 33 hours or less.

My Baja storybegan with a Canadian money trader by the name of Mike Jams, one of the people who pay tens of thousands of dollars to subject themselves to the crucible of the Baja 1000.

Jams had a lifelong dream of going off-road racing. To make that happen he enlisted Baja veteran Ron Stobaugh’s Desert Race School, which teaches people to do exactly what its name implies. Plenty of people come through Stobaugh’s classes for fun or corporate team-building exercises.

When Jams wanted to take his off-roading to the next level and actually compete, Stobaugh and company put a complete package together to teach the Canadian not only how to drive, but how to run a race program in Mexico.

Why start at the Baja 1000, the highest level of intensity? Ron’s reply was simple and truthful: “Nobody here’s getting any younger!”

Stobaugh and I met more than a year ago at a tire demonstration in Malibu. Somehow I impressed him with my impetuousness by submarining a rented Jeep Cherokee in Nitto Tire’s photo-op mud pit, so he invited me to his son’s race at Johnson Valley the following weekend and we’ve been friends ever since.

Stobaugh and company had been training Jams in everything from recovery to the complex logistics of moving a race team around Mexico to driving a car through the desert at speed.

Jams was relatively inexperienced off-road, but he was eager, as well as extremely competitive and analytical. At 51, he was not young though, so Stobaugh wanted to get him seat time in the Baja 1000 as soon as he was ready. Or close to ready. This year, they decided he was close enough to race.

Tires were ordered, a race truck was rented, and a battle-hardened team was assembled. The plan went thus: Jams would drive the beginning and end of the race with three different navigators swapping out, while other drivers and navigators would take up various other sections of the course.

Stobaugh and I would be part of this convoy, jumping in about a quarter of the way through the race. A big group of his friends and family would track the race car via satellite, dispatching help as needed.

Now when I call Stobaugh a “Baja veteran,” that doesn’t mean he goes to Cabo to crush beers and do donuts in his Ford Raptor a couple times a year. I mean, he does that too, but his experience with desert racing and the off-road industry is deeper and more diverse that almost anybody else in the sandbox.

He’s run parts supply companies. Done adventure tours. Managed logistics for massive desert races. And more to the point, he’s actually taken home trophies from the Baja 1000.

He looks the part too; you’ll almost always catch him in the unofficial desert racer uniform of a black t-shirt, tattoos, unnecessarily aggressive sunglasses and a flat-brimmed ball cap. But Stobaugh’s success really stems from his attitude. The guy’s incredibly upbeat. That makes him nice to be around, but more importantly it fuels his resourcefulness, a much needed quality in this race.

See, the Baja 1000 isn’t over when you wipe out. You have to dig, heave, dodge, pull, and think your way out of problems in the pitch dark when you’re exhausted and parked in a stampede of 700-horsepower steel wildebeests.

If you can stay stoked through pain and stress, you might have have a shot at being half-decent at desert racing. But if you can’t, spare yourself from the worst vacation ever and stay out of the car.

I’d never expected an invitation to join Stobaugh on something as high-stakes and high-speed as the Baja 1000. But you don’t decline an opportunity to get embedded in motorsport history. You say Yes, please, and thank you, also can I borrow a racing suit? and you do whatever it takes to convince your boss you need a week-long leave of absence.

So off we went on a pre-run expedition to scout the course, followed by a brief break to get a good shower. Then we were back over the border to take on the 2015 Baja 1000.

“You won’t have to do anything,” I was promised. Or, specifically; “Ron pretty much knows where he’s going. Just hang on and don’t puke. Tell him where the big dangers are.”

The desert proved us wrong.

You Ain’t on Vacation, Boy

Desert racing is the fiercest and most exciting competitive sport no one gives a shit about; we as a nation are too busy obsessing over spandex-clad guys chasing balls across manicured lawns to follow anything this extreme. Teams working together against time, nature and each other in conditions you won’t believe exist on a planet that supports life.

People live for this kind of racing. And shockingly often, they die for it. The two biggest annual off-road racing events on Earth, the Baja 1000 and Dakar Rally, both killed competitors in 2015.

That adds an air of portentousness that becomes palpable on race day.

For about 360 days a year, Baja’s just plain fun. It’s adventure. It’s turning tacos into farts. Crushing cockroaches with the bottom of your Tecate can. Laughing at your buddies when they get stuck in a silt bed.

But when a World Desert Championship event is on, everybody hunkers down and sobers up. Literally.

Suddenly you can’t shrug off a missed turn; it might mean thousands of dollars down the drain. You can’t laugh about saying “left” when you meant “right”; it could kill somebody.

The 24 hours ramping up to race time didn’t feel like the cliché spring break Mexico I’d experienced before. This was tighter. Purposeful. Business Mexico, not Party Mexico.

What An Adorable Little Racing Truck!

Our truck, when we started and how we ended.

Like all forms of racing, this car costs an absurd amount of money.

Even if you can afford to buy one, there’s no good reason not to rent first. You can start at a lower power level than what you might want to end up in. It relieves you of the headache that comes with keeping a car in compliance with race rules. And if you rent from Rick L. Johnson’s Trophy Lite lineup—as our team did—your car comes with a downright heroic maintenance and recovery team.

Race car renters are some seriously unsung heroes in the world of motorsport. A lot of wannabe racers dive into the game buying up the best of everything and hoping for great luck, but the smart money’s on renting something a little slower and the support staff the comes with it.

Even renting is still a rich man’s game; it’s about $2,000 a day starting to borrow a Trophy Lite and you generally can’t do it without any proven training or experience. But it’s a small fraction of what you’d pay to buy a vehicle outright—even though you’re still on the hook for replacing inevitably broken body panels. That’s racing, though.

Two-hundred thirty-nine vehicles ran the 2015 Baja 1000. But even though they might have rubbed fenders on the same course at the same time, they weren’t exactly all racing against each other. It’s divided into “classes” that are basically defined by what engine and chassis competitors allowed to use.

Trophy Lite, known in the Baja as “Class 3000,” is a small (111-inch wheelbase) frame wrapped in a fiberglass body that looks vaguely like a first-generation Chevy Colorado. This was our class. The R-4 variant we were running uses a GM four-cylinder engine that pushes about 200 horsepower through a manually-shifted automatic to the rear wheels. Shock travel is 18 inches front and rear, tires are 33 inches all around.

I was introduced to the navigator’s seat for the first time by Stobaugh while the car sat about a hundred cars deep in the starting lineup. I squeezed myself into the seat and realized there was no windshield, just a narrow slit to see through, like a tank. It was then that I realized I really had no idea what I was getting into.

“This tube will breathe for you,” I was assured. It plugged into the car’s ventilation system with what looked like an old vacuum hose. “Don’t forget to turn on its fan!”

Stobaugh went to talk to someone else and Johnson leaned into the cab, going through essentially the same routine. I paid attention.

My fear of being hurt was negligible next to the thought of failing the driver, the team, and/or somehow cocking up this very expensive and involved operation for the rest of my compatriots. That, and getting dirt all over my fresh t-shirt.

The Trophy Lite looks bigger in person than it does in photos, but it looks like a dinghy lined up next to the Trophy Trucks and Class 1 buggies driven by the most elite competitors in the race. Those vehicles also have more than double the Trophy Lite’s horsepower. A lot more.

Excitement Begins; You Can Finally Start Waiting

At 6 a.m. on November 20th, the 2015 Baja 1000 kicked off.

We were awake shortly after to finalize details for the day and start drinking. Gatorade and water, this time.

Six a.m. is when the first motorcycles began the race. Vehicles carry on from there, in approximate order from fastest to slowest, at 30 second intervals with gaps between classes. Our Trophy Lite would leave the line at about 1 p.m. with Jams at the wheel and Shannon Boothe from the Desert Race School riding co-driver. The rest of the gang and I just had to be ready to fuel them up and dust them off about 80 miles down the race course, which could be reached in only a few minutes on the main road.

We took our bonus time to compose ourselves and enjoy the only decent coffee in Ensenada. All around us the town was lighting up with the crackle of unfiltered race car exhaust noise and kids high on Monster Energy screaming with paws full of stickers. Twenty-three helicopters circledoverhead to get photos, facilitate race logistics and help the competitors that had hired them. Like I said, Business Mexico.

By the time our star racer Mike Jams and his first co-driver Shannon Boothe left the starting line, I was already a quarter of the way down the peninsula with Stobaugh and several other team members, getting ready to receive our racer for their first refuel and co-driver swap.

The Waiting Is The Hardest Part

As we awaited our drivers, the excitement of the affairkept me pumped for the first hour or two. Eventually reality and boredom threatened to set in, but then another cool car would snap by and I’d get a hopelessly blurry photo.

Then I’d get bored again.

Here’s what it’s like to wait for a race car at Baja, assuming my anecdotal experience is the norm:

- You have a vague idea of when your car is getting to your spot, but you’re never really sure.

- You have a radio, your race car has a radio, but one or both of them will be just fritzy enough produce unintelligible messages between parties (or maybe that’s another guy on the same frequency?). So you’ll know you’re confused.

- The race car’s tracked by satellite, but you need an internet connection to see its position. You won’t get good data coverage on the Baja peninsula, so that’s not too helpful. You could use a satellite phone to call your base camp and find the race car’s position, but that’s expensive, and when you do break down and try it, the online tracking service will be down.

- Meanwhile more than half of the cars that come by your area willsound and look exactly like your car from a distance. They will not be your car. You can sit back down.

- Until it is your car, and you think you’ll get the satisfaction of an explanation as to why they’re so late. But the drivers are too tired to manage anything above grunts and you’ll be lucky if they can articulate what needs patching and how much fuel is left.

With every pit stop, this gets worse and worse. The race car gets further off schedule, the more abstract your idea of where they are at any given time becomes, and the more opportunities you get to eat roadside tacos you’re almost definitely going to regret by the time you get in the race car. If you get in the race car.

At about 9 p.m., Stobaugh and I were getting ready to take our shift, 250-ish miles of fairly technical low-traction slop from the east coast of the Baja peninsula to the west. But would we get our chance? We all hovered under the flickering fluorescence of a backwater gas station weighing outcomes and speculating the status of our racers. Fifty meters away another team was rebuilding a transmission.

By 11 p.m. I’d already had more rounds of excitement than I could count on two hands, been through even more rounds of sidewalk tacos, and almost forgotten what the hell I was even doing in Nowhere, Mexico with a bunch of greasy bearded guys.

Then There Are Sparks in Your Pants

The race car rolled up a little after 11 p.m., or about 16 hours into the day, looking nearly flattened, like the Hot Wheels your mean cousin took away and stepped on. Driver and co-driver writhed their way out of the cockpit and onto the deck. Breathing, at least.

A lot of talking and movement. I heard “We fuckin’ rolled it” and the sound of tools clanging from the drawers of a utility bed. Only three of the Trophy Lite’s eight headlights were still piercing the soupy fog that had set in over our quadrant of the peninsula.

“Get your helmet on and get in!” somebody barked, softening it with “Just like we showed ya.”

Adrenaline rush number 15, at least, kicked in and guided me to the seat I’d call home for so much longer than I would expect or want.

Stobaugh was already strapped and fiddling with controls as I struggled with my seatbelt. Race cars don’t get a regular clip-in like your Camry, it’s a five-strap affair that seems tightest across your genitalia with aggressive efficiency.

My next order came someone on the hood of the car, as another man threw a blanket over my freshly-cinched crotch and dropped the full force of his upper body on top of that.

“Shut your visor, shut your eyes.”

The buzz of a welder was unmistakable, if a little muffled through my helmet. Oh hey, my lap is showered in sparks, I thought. They were welding the light bar back in place six inches from my head.

“What kind of condition is the car in?”and “Any new pulls or wobbles we need to watch out for?” and “Has the structural integrity been compromised?” were all questions I would have loved to have asked, but my brain wasn’t coming up with anything outside of holyshitholyshitholyshit.

The brief diagnostic period we did get let us figure out that the secondary GPS was dead and the intercom was malfunctioning. Stobaugh could hear me, but I couldn’t hear him. “It’s fine,” he told me. “You just read me the map like we talked about. We’ll figure it out.”

Of course we would. And with my span of control limited to the “zoom in” and “zoom out” buttons, how much trouble could I possiblyget us in?

Let’s Do This

“Hands clear and GO GO GO!”

For the first five seconds, my excitement was deafening. I’mracingtheBaja1000!

Six seconds in I was freezing. Seven seconds in I was filled with anxiety. Christ, would I be this cold the whole time? We’re really going fast. Sure hope this GPS stops flickering. When do the turns come and I get to talk? How far ahead do I call the turns? Are all the turns even worth mentioning?

Finally: This car sure is wobbly on pavement.

Forty miles an hour never felt faster to me than in the right seat of that Trophy Lite in the Baja 1000. That’s because the car was never going the same direction for more than two consecutive seconds.

We plowed into the night, bouncing off small rocks, bounding over bigger ones, and scraping up against boulders the size of cows. Or was that a cow?

With no guidance from my mute driver, I came up with my own system for reporting the terrain ahead and hoped he liked it.

The dangers we’d marked the previous week pre-running were conveniently labeled. Things like “HOLE ON RIGHT” or “ROCKS” were simple, I’d just read them. Turns were a little less clear. I had to decide, based on a squiggly line bouncing around the corner of my eye, if a turn looked sharp enough to warrant warning Stobaugh about, then assign an arbitrary designation of severity with which to describe it.

I started out with “soft,” “medium” “sharp” and “extremely sharp” as descriptors. That seemed to work out, as we weren’t crashing, but then I started realizing some of the turns were long sweepers while others were much more abrupt. I needed a way to describe those too. Settled on “short” and “long.” Hope that helps you, buddy!, I thought but didn’t say, fearing any unnecessary distraction of the driver would kill us or otherwise end our race effort in shame.

The GPS had a scale, which I used to assign a vague range of how far marked obstacles and turns were. I stuck to reporting at what I thought looked like 1500, 1000, 500 meters, and finally “very close” when we were pretty much on top of something, then telling Stobaugh we were through, in case I’d made an obstacle sound scarier than it was and it wasn’t obvious if we’d passed it.

It Got So Much Harder

I hadn’t realized it at the time, but hours had gone by before my task became truly difficult. Eventually the track evaporated into the blackness of desert night and I was effectively driving the car with my words.

Describing a turn that follows a defined road is child’s play. You can get away with gripping diction like “Go leftish!” But trying to articulate a specific route through open desert is virtually impossible.

“Turn, uh, about 45 degrees left,” I said. “Ten, no, 11 o’clock?” The car blazed ahead as I floundered. Stobaugh became visibly frustrated; god knows what he screamed into his helmet.

But as defined track revealed itself again and we got back on course, the sea of emotions in our little race car calmed down. There’s no holding grudges in racing. No time for it. The only thing to do after a mistake is to try and correct it. If your methods don’t work, try something else.

Feelings or conversation not directly related to getting toward the finish line have no place in a race car. That includes guilt, so I shook off my poor decisions and pressed on giving the best damn directions I could. Until I couldn’t.

Reality Sets In With Your First Crash

Remember when I told you our Trophy Lite ran 33-inch tires? You probably nodded off through all those boring numbers, but they’re about to become important. The faster trucks blazing the trail miles ahead of us had much larger 37-inch tires, at least. They made the ruts in the silt. Silt that became even softer because a whole pack of 700 horsepower trucks had chewed it up.

So we dropped into a wash and the road disappeared. I was back in full navigation mode again, and stuttering for adjectives. Eventually, we realized it was easiest if I just pointed through where a windshield should be, in some kind of average of where I thought we should go, based on the terrain and where we were relative to the racing line.

Stobaugh picked his way through deep sand and vegetation as best he could with my amateur instruction and nil visibility, but things were degrading quickly.

Turns became forced decisions for the lesser of two dangers: Left is a hole, right looks like a squeeze. Right we go!

Now left looks soft, but right is an impassable drop. Cut left.

All the choices being made in split seconds, one after another, until Oh hey there’s a car stuck there!

A quick turn to avoid a crashed vehicle. Right to avoid a bush, another vehicle in the track. It was either let off the throttle or plow into a mired race car and make a lot of people have a very bad night.

The valiant Trophy Lite wheezed to a stop, completely beached on a crown of silt. The rear wheels pathetically dug into the ground while the fronts hung in the air.

We were stuck in traffic behind a Japanese team I recognized from the starting lineup in a strange-looking buggy up to its axles in hopelessness. As our own engine idled I realized what a racket that little thing had been making at open throttle.

Now it was time to dig the truck out. So much for hang on and don’t puke.

Oh Yes, There Will Be Digging

I took what I could from abig surge of adrenaline as we began our first recovery. Whipping out the headlamp I’d stolen from my girlfriend’s camping gear, I took the shovel and traction boards and got to work.

The wheels cleared, Stobaugh mashed the gas, and I leaned on the bumper as the car moved. About six feet back.

This surface was softer than anything I’d ever encountered, or would dream of driving on. Drop a tool and it would sink in and disappear. Digging through it was like petting a cat that had just come out of a dryer. And it was sucking up our tiny tires like the last sip of a fat guy’s milkshake.

Mired again? No problem, just keep that shovel swinging. “We’ll get through this.” I said this out loud, to feel a little more useful. Stobaugh was doing a great job staying calm, but who wouldn’t benefit from a some positivity when you’re stuck in the middle of the desert with a strong risk of being run over and killed?

That’s no joke. There are few dangers in racing greater than being stopped and out of your car. This is the exact situation in which Mango Racing’s Monte Droogsma died, just hours after our own first crash. He was hit by a racing car while recovering.

After three attempts to extract our vehicle from the dust bowl, my adrenaline high was beginning to wear off. But in the moment my mood started to sour, I saw a new reason to get fired up. Two, actually; square headlights.

Then a profile noshing through the brush: a lifted O.J.-era Ford Bronco. Just like the one Rick Johnson had brought to Baja to rescue the Trophy Lite.

I scrambled through the sand waving my arms like C-3PO when he spots that giant Jawa tank. Yes, exactly that stiff, because I’d been shoveling for… some amount of time. I can’t remember.

“Hey there, son!” Johnson smiled at me from under his big, beautiful mustache and I was fired up all over again. “Saw on the GPS you’d been stuck for a couple hours so we figured we better come give ya’ a hand.”

Hours? Good god.

With helmets back on, I reengaged the air filter, which belched a cloud of sand into our faces and then started working again. We spent no time nursing wounds or reveling in our rescue. It was back to calling turns and obstacles and coping with a new challenge: staying conscious.

The Taste of Pain Becomes Familiar

The crash I just described happened again. And a third time. One of those times we dug ourselves out with the help of some friendly overlanders on a camping trip, the other, we fought fruitlessly against the sand with our shovels until Johnson and his Bronco showed up to yank us out. Each recovery was even more spectacular than the crash that led to it.

The crashes took their toll on our machine. Damage to the truck’s fiberglass was steadily creeping toward the front of the vehicle, like a big hungry sand monster had been gnawing away from the tailgate forward.

Worse than crashing was the threat of fatigue. In a race, being too amped is almost as dangerous as being exhausted. But that energy gets vacuumed up as quick as your brain can manufacture it.

I vividly remember effectively waking up, realizing the car was stopped, and seeing our pit crew fiddle with things as somebody told us “it’s 5 o’clock in the morning.”

Oh hey, look at that, I thought. Sun’s coming up and it’s November 21st.

Just a little longer. Really, a lot longer. But this was no time to dwell on that. We moved on.

Meet Your Breaking Point, Then Pass It

Then we crashed again. The fourth crash was the one that broke us, left us shells of men.

This one happened well past our limits. With a shame I’ll never shake, I’ll admit that in that moment I wanted to quit. Stobaugh’s own anguish was as easy to see as the dirt all over his suit.

The Trophy Lite was “fine,” I suppose, in the sense that the roll cage was intact and the drivetrain was still operational. But the desert had stripped it of fiberglass body panels, tools that had been strapped to the side, and much of the armor covering the underside.

Once brand-new tires now looked like they had a hard decade’s worth of wear on them, and about a third of our lights had been snagged by stubborn branches somewhere in the sand.

Whether or not to quit was Stobaugh’s call to make, but I was afraid my faintest suggestion of bailing might push him over the edge. If that happened, I’d always blame myself for our ultimate failure. Then again we were still hours from the end of our section and…

Suddenly, the sound of feeling sorry for myself was clipped.

I’d love to tell you that I reached down and pulled some superhuman sense of motivation out of the dirt. Or that I could simply sack up and get the job done because it needed doing. Nah, something else was singing to me, stirring my soul.

The V8 rumble of that motherfucking Ford Bronco.

Bring It Home on Your 10,000th Wind

Johnson and his crew heaved us out, tossed us a couple Gatorades, and hovered behind us while we rode back into battle, our positive attitudes and the last spark of life in our race car both stoked back up.

But somewhere between that last crash and the next checkpoint, I simply disappeared. Hallucinations be damned, I had transcended into a full-on vision quest in the right seat of a race car running at speed.

It was warm where I was, and everything was white. Pillowy, like a cartoon version of heaven. The brutality of the bumps had softened; it was like being on a large ship at sea, gently swaying.

I had time to take this all in before the jabs came. A punch in the chest. Another. There was some kind of siren, maybe yelling?

Nope, just the relentless wail of that engine thrashing heroically against redline through another soft section of race course. And those hits were Stobaugh stabbing the brake.

Hilariously, a substantial chunk of cactus was bobbing back and forth on the hood. My driver was trying to outsmart it by diving the vehicle and sending it over the edge. But he gave up when we needed to boot it through more sand, and of course the desert got its way. Fuck that cactus.

We cleared hoursmore before hitting the last speed zone on a gravel road south of San Felipe. When we finally got on flat ground and the chaos eased, I was too tired to feel relief. Too apathetic to give a damn that we were going to finish after all.

Then our left rear tire exploded.

But We DidMake It

Thanks to the kindness of another passing race crew, we were able to get our truck jacked up and the dead tire swapped for our spare. Our own jack had been torn off somewhere between our present location and the first place we got stuck, hundreds of miles and two eternities ago.

At about 3 p.m. on November 21st we handed the race car off to Stobaugh’s son Austin to do another 200 miles. He would hand it off once more to Mike and co-driver Dan Goldberg to finish out the race.

In order to get on the scoreboard at the 2015 Baja 1000, you had to finish the race in 33 hours. Our team dragged our steaming heap of steel and what few bits of fiberglass body it had left to the end of the race at 36 hours.

The truck was still driving under its own power, structurally sound, and under some very scarred skin somehow still ready to run. But it looked like a toy left in a preschool sandbox for six years.

The few chunks of the body that hadn’t been decimated were held together with tape. The Canadian/American flag graphic on the hood was totally Jackson Pollock’d with dirt, dings and oil stains.

Jams was visibly frustrated that we didn’t make it over the line in time. As he cracked a hard-earned Tecate, I found out our boys were so smoked in that last leg that they ended up driving the wrong direction on-course for a few miles. Good thing we were at the back by then, and I guess even luckier that they brought most of the car back to Ensenada at all.

As for Stobaugh, with all his people accounted for he finally allowed himself to power down. Experienced as he is. there were no bones made about it; 2015 was the meanest he’d run.

“We almost died together, man,” he said, while insisting on covering my bar tab.

This won’t be his last Baja, though. Far from it. Desert racing is a part of him, sometimes literally when his skin is covered in more sand than tattoos. By the time this story is published he will have helped organize and execute more racing efforts and entire events and I suspect he’ll be driving hard until the day he drops.

I hope it’s not my last Baja either.

It took days to process what had really happened. There was the thrill of speed and competition. The fear of disappointing others and dismemberment. But more than anything I remembered the pain.

Being stretched that far out of my comfort zone for so long was well beyond what I could have imagined before this experience. After I’d committed all the mental and physical resources I had, the situation took more.

Plunging deep into unprecedentedly profound despair, and then knowing you’ve beaten it, is a glory unparalleled. That’s what those gas-guzzling cowboys are chasing when they run the Baja 1000.

I finally get it. I hope you do too.

Top graphic credit Sam Woolley

Images by the author, SCORE International, Curtis M/YouTube, TROPHYLITE/YouTube, Nitto Tire/YouTube. Some images are for illustrative purposes only. No room for my camera in the car.

Contact the author at andrew@jalopnik.com.